The long shadow of systemic racism continues to harm generations of Black agricultural communities that face entrenched economic obstacles to success.

Eugene “Butch” Flenaugh, Jr. came back home to Phillips County, Arkansas about five years ago to care for the family’s farm in the Mississippi River Delta bottomland. Today, when he looks out over the 400-plus acres that his family owns, he’s often nostalgic about the stories his father told him when the entire Delta River flatland was tilled and owned by Black farmers and sharecroppers as far as the eye could see. After World War I, he says, many came back from fighting overseas and began to purchase the flood-prone land along the Mississippi River basin that white farmers thought was inferior.

The Flenaughs’ property, nearby Holly Grove, and the former all-Black towns and communities date back more than two centuries. Flenaugh and every Black farmer, former sharecropper, and landowner across the Delta whisper about the missing, lost, or sham property deeds at the Phillips County Courthouse at the county seat in Helena. According to state officials, the county is one of just three in the state that don’t have public online access to court and property records.

All those deeds link to the ghosts of the Elaine Massacre of 1919, which is by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas and possibly the bloodiest racial conflict in U.S. history.

The events in Elaine, almost 103 years ago, stemmed from the state’s deepest roots of white supremacy, tense race relations, and growing concerns about labor unions. In September 1919, a shooting incident that occurred at a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union—a Black-led organization that sought to improve life for Black farmers and communities in the state—escalated into mob violence by white people in Elaine and the surrounding area.

Although the exact number is unknown, estimates of the number of African Americans killed range in the hundreds. Only five white people lost their lives, according to records from the time. Even so, 12 Black men were arrested in the wake of the white-led massacre and sentenced to death for murder charges. The Elaine 12, as they came to be known, became part of a precedent-setting legal case with nearly as long an impact as the massacre itself.

Flenaugh says his family’s land goes back to his great-grandfather, Cebron Johnson (Hall), who in the 1880s left more than 30,000 acres in Monroe and Philips counties to descendants and their families just east of the former all-Black town of Holly Grove. That land, according to Butch’s father, Eugene, Sr., was owned by the family prior to the massacre as Black farmers emerged from slavery in the late 19th century.

“This is part of that 30,000 [acres],” says the younger Flenaugh, a well-built, 50-year-old farmer, as he looks out over property that is part forest thicket, part nature preserve, and part family graveyard.

Photo credit: Wesley Brown

What happened to the Johnson land is a fate that befell countless Black farms during the early 20th century: Land was taken through outright theft, intimidation, violence, and fraudulent property records, with the end result of robbing generations of Black families from the inherited wealth that comes from land ownership. And at a time when the current administration has committed to advancing racial equity, and efforts to provide debt relief to Black farmers have been stymied by racist lawsuits, the scale of violent land theft is coming to light in a powerful, galvanizing way.

A Century of Land Theft in Arkansas

Getting to the Flenaughs’ plot of land in East Holly Grove confuses both Alexa and GPS. Driving 15 miles on winding Arkansas Highway 146 takes you past the Big Slash Hunting Club, which locals call “Jurassic Park” due to the habitat’s well-maintained property, state-of-the-art security, and 10-foot barbed wire fence that screams “no trespassing.”

According to a recent real estate listing, the 1,650-acre preserve is up for sale for $11.1 million; that price tag includes diverse waterfowl habitats such as flooded green timber, tupelo and cypress brakes, wetland slashes, and more than 600 acres of agricultural fields.

Meanwhile, most Black farmers’ experience in the region is similar to the Flenaughs’. When he first got to his family’s place, Flenaugh says there was no wildlife in the area because the rice farmers adjacent to the family’s property had killed off everything with pesticides. Once he stopped the white farmers from spraying the chemicals on his family’s property, Flenaugh’s land recovered. Today, it is brimming with life; a wide variety of waterfowl make the region part of the “Duck-Hunting Capital of the World.”

Photo CC-licensed by Jimmy Emerson on Flickr

“I can now walk out on my stand and see the same duck and waterfowls, big game deer, wild pigs, snakes, catfish, and other wildlife that can be found over there at Big Slash,” says Flenaugh.

The novice farmer told Civil Eats that the legacy of the Elaine Massacre is still “thick in the air,” because everyone knows that thousands of acres of land that are now in the hands of white and corporate landowners once belonged to Black farmers.

“It doesn’t make any sense, because if you go look at the records over the years, they kept changing the [property] books,” he says, adding that most Black families were driven off their land or “scattered” during the Red Summer of 1919.

“If you look at those records, those whose [names] were penciled out just disappeared; those that had red marks were burned on their land or in their houses. The ones that had blue check marks on them are the ones that they were after, or they just left and never came back,” he says.

“The sad part about it is that every last bit of property around here is ‘heir property.’ If more people understood that, they could come back and get [their] land.”

According to a 2019 report by the Equal Justice Initiative, the racist attacks in 1919 were widespread and targeted the 380,000 Black veterans who had just returned from the war. “Military service sparked dreams of racial equality for generations of African Americans,” the report notes. However, “during the lynching era, many Black veterans were targeted for mistreatment, violence, and murder because of their race and status as veterans” and the perceived threat they posed to Jim Crow and racial subordination. The report goes on to note that “racial violence . . . reinforced a legacy of racial inequality that has never been adequately addressed and continues to be evident in the injustice and unfairness of the administration of criminal justice in America.”

Flenaugh says the Elaine Massacre sent a message of intimidation that still affects the region today. And there are still some Black and white people who say the incident should not be talked about, even after a local committee dedicated a memorial to those slain during the 100-year commemoration two years ago.

“The sad part about it is that every last bit of property around here is ‘heir property.’ If more people understood that, they could come back and get [their] land,” he says.

Yet Flenaugh’s own family is still in a fight to keep all their land. Flenaugh and his father, Eugene Flenaugh, Sr., and two brothers, Johnathan and Eric, had a court date this summer at the Phillip County Circuit Court in Helena-West Helena concerning property line dispute with a white farmer seeking to plant rice on their plot.

The tense struggle has led to confrontations with the Phillips County Sheriff’s Department and bad blood with the white farmer. In June, the court allowed the white farmer to plant on the disputed land, but the complaint still has not been fully settled. Larry Hicks, a Little Rock-based NAACP attorney who has taken an interest in the Flenaugh’s case and the plight of Black farmers in Arkansas, said the family recently sent a letter to the court terminating the legal services of their attorney following the court hearing in late June.

For the Flenaughs, the dispute bring up memories of Elaine and the repeating patterns of stolen Black wealth. “We just want them to leave us alone,” the elder Flenaugh told Civil Eats.

Working to Return Lands to Black Families

One month before Flenaugh’s hearing, Lisa Hicks-Gilbert of Elaine entered the same Phillips County courthouse to research what happened to her relatives’ land. She first learned about the massacre in 2008, while studying to be a paralegal, and discovered the book Blood in Their Eyes.

In hushed conversations with her grandmother, she learned that she had a personal connection to the massacre: She was related to three of the Elaine 12, including Frank and Ed Hicks. The story goes that Frank had two families—one with his first wife, who died at an early age, and another after he remarried. Hicks-Gilbert says she is a granddaughter of one of the first sons but she has been trying to track down more information about that side of the family since her grandmother passed away in 2019, on the 100th anniversary of the massacre.

Hicks-Gilbert says she promised not to speak publicly about the massacre while her grandmother was alive. Now the caretaker of the Descendants of the Elaine Massacre Facebook group, Gilbert is on a mission to make sure that the heirs’ property belonging to Black descendants of the Elaine genocide is restored to its rightful owners.

Lisa Hicks-Gilberts. (Photo credit: Wesley Brown)

“The biggest endeavor we are working on is creating a database of all those killed and the survivors. We’re going to open it up [to the public] because we know that in finding records and talking to families, a lot of them [left town] during the massacre. They were scared,” says Hicks-Gilbert.

She adds that many Black families and single men who didn’t migrate to the Midwest or East stayed on as sharecroppers in Arkansas or left for states like Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. Once there, they often sought out anonymity.

“I found one family that changed their last name after their grandfather escaped,” says Hicks-Gilbert.

On that day at the courthouse, she learned that her great-grandfather’s brother, Ed or Edd Hicks, one of the Elaine 12, lost his land to a white landowner just two months after he and the eleven other Black men were jailed and charged with murder and condemned to death by all-white juries.

Hicks-Gilbert says that seeing the deed itself helped her understand the “transgenerational trauma” she had seen in her grandmother’s face every day while she was alive. “She was friends with survivors who were in the choir with her, who went to church with her, and they all shared in this tragedy,” says Hicks-Gilbert, wiping tears from her eyes. “And I look at it now; it was all about surviving.”

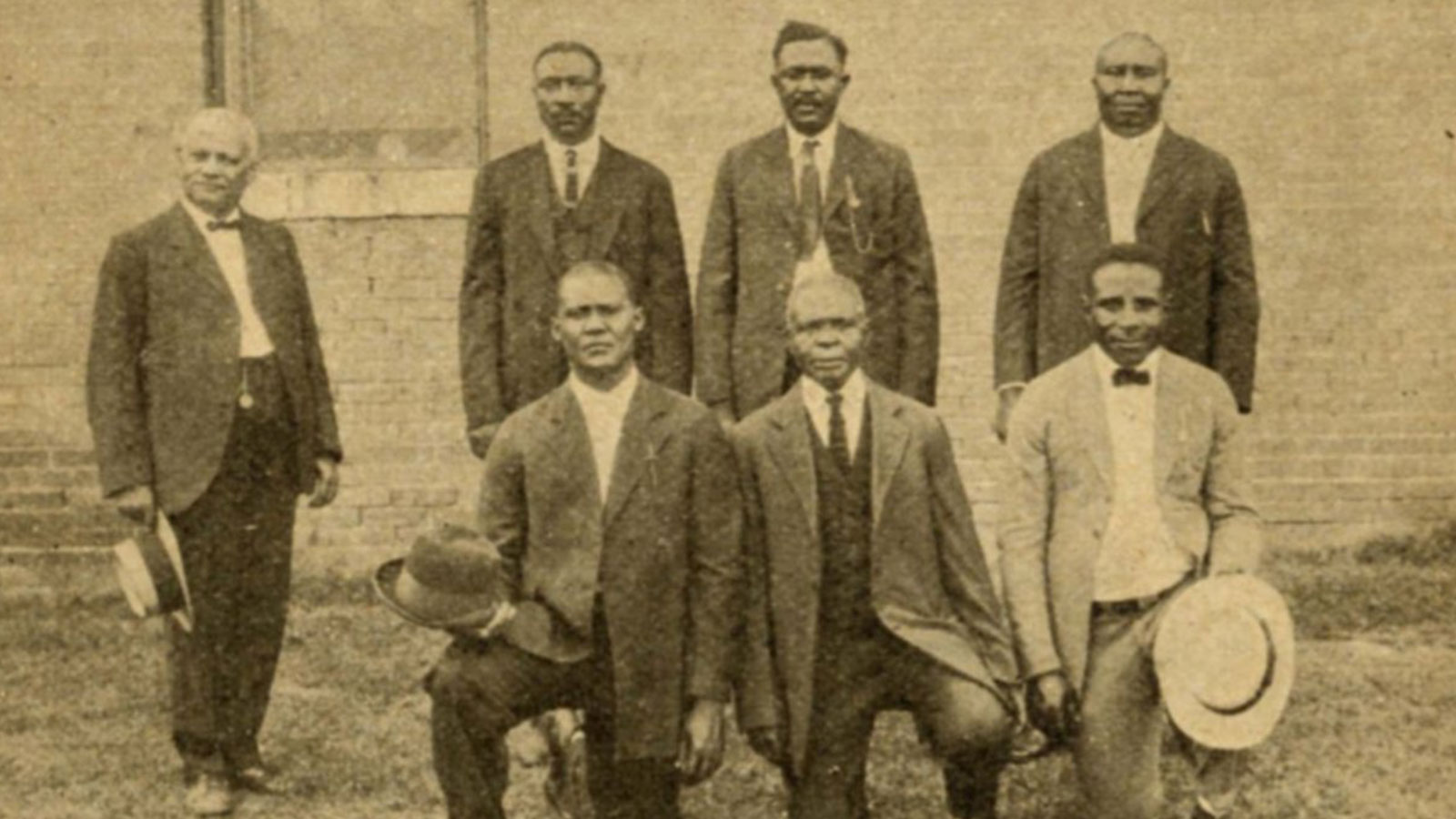

Six of the Elaine 12 circa 1923: S. A. Jones, Ed Hicks, Frank Hicks, Frank Moore, J. C. Knox, Ed Coleman and Paul Hall. Scipio Jones is at left. (Photo courtesy of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System.)

Like Flenaugh, Hicks-Gilbert says the massacre was meant to put fear in the hearts of Black farmers across the Arkansas Delta.

Hicks-Gilbert’s main goal is to get an accurate count all the Black people killed during the massacre. In tracking coverage and mentions of the incident over time, she has noticed that white newspapers have often minimized the Black death toll. At first, local law enforcement set the official number at 26. In the years afterward, however, some estimates have swelled to well over 800.

“When I get with other descendants, we’re talking, and everybody’s stories are syncing up, we know there were upwards of a thousand [deaths],” says Hicks-Gilbert.

She also believes the ghosts of the Elaine Massacre are responsible for the feeling that time has been standing still in Philips County for the last 100 years. She points to the fact that it still has the state’s largest Black population, but the median household income of $33,724 is 50 percent lower than the national average $67,521, and 32 percent lower than the Arkansas median. It is not only the poorest county in Arkansas but also among the poorest counties in the U.S. by household income.

“At least three generations of Hicks worked on the land that was stolen from my grandfather and my uncle. . . . Black families throughout Phillips County were left with generations of poverty, oppression, suppression, and depression akin to slavery.”

Hicks-Gilbert said the Black sharecroppers that were a part of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union at Hoop Spur were not just fighting for better pay for their crops at the time. They were also banding together to buy land independently, as a path toward community and generational wealth that would have enriched the lives of many Black families in Phillips County and Arkansas.

“At least three generations of Hicks worked on the land that was stolen from my grandfather and my uncle. My brother currently lives and works near Hoop Spur, yet we have never owned any part of it,” she added. “Instead, Black families throughout Phillips County were left with generations of poverty, oppression, suppression, and depression akin to slavery.”

Reconnecting to Farming—and to Racial Justice

In New York City, Hazel Adams-Shango also has a connection to these Arkansas farmers and sharecroppers as the great-granddaughter of Scipio Africanus Jones, the iconic civil rights attorney now getting renewed national attention for his work defending the Elaine 12.

Adams-Shango is a budding urban farmer who began studying hydroponics at the beginning of the pandemic, after she became concerned about food security. Her interest in farming turned serious when she took a class on vertical farming at Farm.One, the crowdfunded, antiracist, and antidiscrimination urban farm in Manhattan’s TriBeCa neighborhood that supplies hydroponic greens and edible flowers to many of the city’s top restaurants.

“It has been calling us all this time; we just had to listen,” says Adams-Shango of her farming roots. She added that her journey into urban and vertical farming brings back memories of her childhood visits to the South with her great aunt, who ran a homestead farm in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

“I would spend summers down there . . . but I had forgotten all about that,” Adams-Shango recalls.

While she was learning to farm, her mother and 103-year-old aunt attended the unveiling of a life-size portrait of her famous great-grandfather. In 1923, Jones filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the Elaine 12 were denied due process of law. After reviewing the case, the Supreme Court agreed and overturned the convictions. The precedent-setting Moore v. Dempsey changed the nature of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause, allowing federal courts to hear and examine evidence in state criminal cases to protect defendants’ constitutional rights.

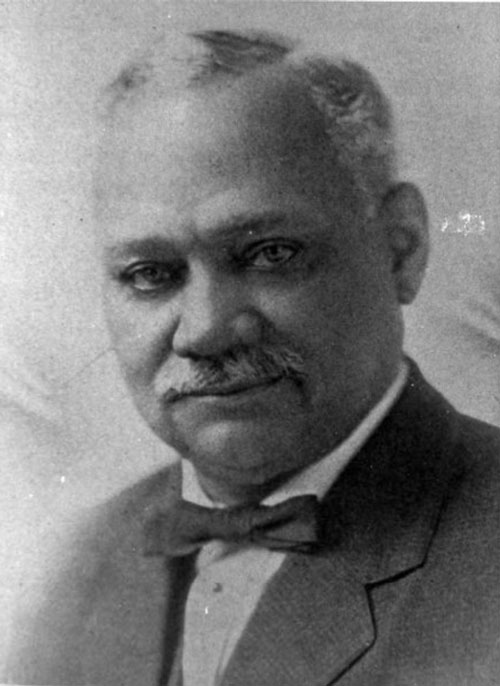

Scipio Africanus Jones. (Photo courtesy of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System.)

For years, Adams-Shango says her mother used to share stories about the famous lawyer, but she only now understands the strong connection to farming. She is also excited about the renewed interest in his life. That interest also led Hollywood’s Searchlight Pictures last year to purchase the rights for The Defender, a biopic about Scipio Jones.

Meanwhile, Adams-Shango is taking a leap and starting a farm with her three adult children, Kofi, Johnathan, and Hazel. After an immersion program at Hartsfield Organic Farm in Vermont, her family found a farm mentor, ordered non-GMO heirloom seeds, and made plans to pay a financial backer $1,200 a year to bootstrap a 17.5-acre plot called The Flying Buffalo.

“I think this can work, and can even do this as a family,” the former Chicago Mercantile Exchange broker explains.

Advancing Racial Equity Nationwide

Returning land, or the wealth that it would have generated, to Black families poses a monumental challenge. This spring, a study out of the University of Massachusetts-Boston showed that Black farmers lost more than $326 billion worth of land during the 20th century.

Dania Francis, the lead author of the study, told Civil Eats that Black agricultural land ownership peaked right after the turn of the 20th century, just ahead of the Elaine Massacre and the wave of others like it. W.E.B DuBois in 1907 estimated that Black families owned 3 million acres in 1875, 8 million in 1890, and 12 million in 1900. By 1910, African Americans had acquired more than 16 million acres. “This was the most land they would ever own in the United States; however, there was a nearly 90 percent decline in ownership from 1910 to 1997,” the report states.

“If you are a landowner, you are more able to send your kids to college; you are more able to invest in other businesses. We didn’t even model that in this estimate.”

Francis said that total represents the most conservative estimate possible. “We don’t include all the additional life-reinforcing value that having that land would create,” she told Civil Eats. “If you are a landowner, you are more able to send your kids to college; you are more able to invest in other businesses. So, we didn’t even model that in this estimate.”

Francis and her team have already started the second phase of the study, which will include research on the potential wealth lost by Black farmers and their families. “We wanted to get this estimate out there first, and now there is this ability to use this land [as the baseline for calculating] capital and grow the [estimate] even bigger.”

The final piece of the study, Francis acknowledged, is moving the national conversation on reparations that was reignited following George Floyd’s murder forward. Francis, who co-authored an influential 2003 paper on “The Economics of Reparations,” said the key takeaway from the 2022 study is that the legacy of slavery and post-Civil War state-sanctioned discrimination and ongoing institutional inequities prevented the enslaved and their descendants from benefiting from the growth of the U.S. economy.

“The work that we are doing has to be done directly in conversation with the work on reparations,” Francis said. “A reparations program should be targeted to the current Black-white wealth gap as a representation of all that harm.”

Francis added that it is important to have an estimate for not just Black agricultural losses but for “all the individual harms” that have impacted African Americans, including slavery, lynching, housing discrimination, and racism in the criminal justice system.

“Not that we are going to add up all those harms, but it helps provide more evidence to say, ‘Look, this has dollar value,’” said Francis.

For descendants like Flenaugh, Adams-Shango, and Hicks-Gilbert—and their families and communities—that’s an important step forward.

Source: Civil Eats

Featured image: Eugene “Butch” Flenaugh, Jr., on his farm in Arkansas. (Photo credit: Wesley Brown)