By Calvin Schermerhorn, African American Intellectual History Society —

This is an excerpt from Calvin Schermerhorn’s Unrequited Toil: A History of United States Slavery (Cambridge University Press, 2018). This excerpt has been reprinted with permission.

African-descended Americans bore the social costs of slavery. They paid several times over, in fact. They paid at the point of sale when children were stolen by strangers, when parents were snatched up by slave traders, or when spouses were separated at sheriffs’ auctions following owners’ deaths or business failures. Enslaved people forfeited social capital when separations prevented ancestors’ wisdom and knowledge from being passed to the next generation. They paid with ruined health. Their bodies were bruised, broken, or raped through machine-tooled violence in the fields and under their roofs, tears of anguish and humiliation running down the generations. They paid for the pernicious myth that dark skin was inferior to light – that African ancestry was lower than European. And they paid with the generations-deep theft of wages, stolen inventions, and unrepaid investments in mastering the skills that produced millions of bales of cotton and other goods and commodities. Yet enslaved people did not simply struggle along with the forlorn hope of a better day.

They unfastened chains as solitary fugitives and as armed rebels. Some stood up to individual owners and overseers. Others joined invading forces. In each generation, handfuls picked up books and took up pens, using hard-won literacy to publicize African Americans’ protests and visions of liberation. They worked to undermine slavery’s laws and political support. In quiet places of worship, they developed new theologies, new ways of knowing, and new ways of narrating their world. African-descended artists set about creating literature, music, and poetry, fundamentals of American culture. The shared experience of forced labor bound many together, but the unruly strategies of enslavers tended to pull bondspeople relentlessly apart. Slavery was never one thing, and enslaved people were never homogenous. There was no stagnation or sleepy plantation. There was precious little community. And never before did slavery transform in such a short time and within one political nation as in the United States of America.

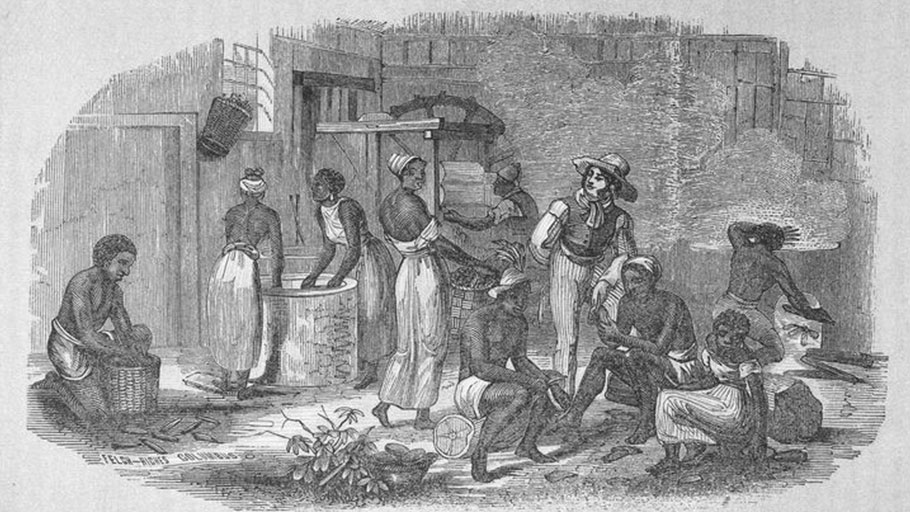

Cotton capitalism stood at the center of US slavery, but it was one among many variations over space and time. There was never one Slave South but “many Souths,” each with differing kinds of slavery.1 Work varied by region and social situation. Some bondspersons labored in city factories or urban dwellings. Others grew grain, sawed timber, smithed iron, milled flour, or caulked ships’ hulls. Some cultivated rice in the swampy Lowcountry while others staffed Louisiana canebrakes.

Bondspersons served plates of food or drove wagons, and worked on steamboats or in railroad gangs. Some were forced to perform sex work. The young pulled weeds and tended cattle. The aged cradled babies and groomed horses. And their toils changed over time. Cotton slavery, along with nineteenth-century African American language, folklore, and religious persuasions, would have been unrecognizable to the first African arrivals in British North America in the early seventeenth century. Instead of cotton slavery being normative, it should be thought of as the product of a certain time and place, distinctive in the Americas and indeed the globe, a highly commercialized outcome of a centuries-long process.

Slavery in British North America began when castoffs of a broader Atlantic slave trade arrived in distant outposts of empire. The engine of the transatlantic slave trade of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was sugar and, secondarily, gold and silver. But what became the Eastern United States grew no sugar, and its gold had not yet been discovered. One historian terms the first generations of enslaved people “Atlantic creoles.”2 They arrived in New England, New York, the Virginia and Maryland Chesapeake, and the Carolina Lowcountry. Atlantic creoles were often multilingual, Muslim, Catholic, or adherents of African traditional religions.3 They generally understood the geography over which they were scattered.

Slavery in British North America began when castoffs of a broader Atlantic slave trade arrived in distant outposts of empire. The engine of the transatlantic slave trade of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was sugar and, secondarily, gold and silver. But what became the Eastern United States grew no sugar, and its gold had not yet been discovered. One historian terms the first generations of enslaved people “Atlantic creoles.”2 They arrived in New England, New York, the Virginia and Maryland Chesapeake, and the Carolina Lowcountry. Atlantic creoles were often multilingual, Muslim, Catholic, or adherents of African traditional religions.3 They generally understood the geography over which they were scattered.

On arrival in the colonies, few Atlantic creoles considered themselves African, let alone African American. Those identities took time to develop. Many seventeenth-century arrivals in New Amsterdam were from southwestern Africa and arrived speaking Kongo or Mbundu as well as Portuguese or Dutch. Some arrived from Madagascar. Others were already creolized, re-exported from the Caribbean or Brazil. The English conquered New Amsterdam in 1664, and New York became the biggest slave colony in English North America in the seventeenth century. Until 1700 more African-descended people lived in New York than in Virginia or South Carolina. In New York, African-descended bonds-persons tended to work on small farms or in trades and transportation.

Things were different farther south. Virginia’s earliest African arrivals were also from southwestern Africa, and a few worked their way out of slavery to become small landowners. Many toiled side by side with unfree indentured servants, poor Englishmen and women in tobacco fields with whom some made common cause. But in seventeenth-century South Carolina, most enslaved people were not even African-descended. They were captured Indians, taken from confederacies reaching as far west as present-day Arkansas, exported from Charles Town to destinations like Boston and Barbados.

In the seventeenth century, the English North American colonies were societies with slaves as opposed to West Indian slave societies, the difference being that societies with slaves were places in which slavery was marginal to economic activity and political institutions. Laws and customs tended to keep enslaved people in chains, but they had some degree of mobility and did not seem a grave threat to domestic security. During the eighteenth century, patterns changed.

The Chesapeake and Carolina Lowcountry emerged as slave societies in the decades after 1700. South Carolina enslavers shifted from exporting captive Indians to exporting rice. To do that they began buying Kongo and Senegambian captives (embarked from present-day Angola, Senegal, and Gambia) to toil in rice fields. As soon as the colony began importing Africans, South Carolina passed laws giving enslavers private authority to maim and kill in the name of discipline and security.

In the eighteenth century, Chesapeake tobacco planters replaced English indentured servants with imported Africans, this time from the Bight of Biafra in present-day southern Nigeria and Cameroon. Perhaps four in five were Igbo. Unlike Atlantic creoles, these bondspersons were captured from the forested interior. Captives did not arrive speaking English or other European languages, but they did carve out distinctive cultural spaces on plantations. And by the time George Washington was born in 1732, Virginia was a slave society exporting tobacco. Like the Carolina Lowcountry, Tidewater Virginia relied on its black majority as the labor backbone of the staple crop.

In slave societies, owners and managers intensified violence to boost productivity, mitigate rebelliousness, and prevent uprisings. Virginia passed laws permitting enslavers to inflict disfiguring punishments on bondspersons while requiring poor whites to perform militia service, policing the colony’s growing slave population. At the same time, New York and the mid-Atlantic colonies north of Delaware relied less on slave labor. Their slave laws relaxed or fell into disuse, yet racial designations did not. Anti-black racism followed slavery’s development but did not unfollow its decline. As Virginia and South Carolina became slave societies, they drew a rigid color line. Any person of African descent was presumed to be enslaved. From the Lowcountry to New England, as one historian puts it, “racial exploitation and racial conflict have been part of the DNA of American culture.”4 And as they invented racial slavery, Americans were quickly commercializing it. That made it distinctive in both North America and the Atlantic world.

- William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion, vol. 1: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990), 35.

- Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 29

- Stephanie Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008).

- David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006), 226.

Calvin Schermerhorn is currently Professor of History at Arizona State University and Associate Director for Undergraduate Studies in the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies. He is the author of several books, including The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860 (Yale University Press, 2015). His new book, Unrequited Toil: A History of United States Slavery, was published by Cambridge University Press. Follow him on Twitter @CalScherm.

Featured image credit: Schomburg Center Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books, History of Slavery and Slave Trade Collection.