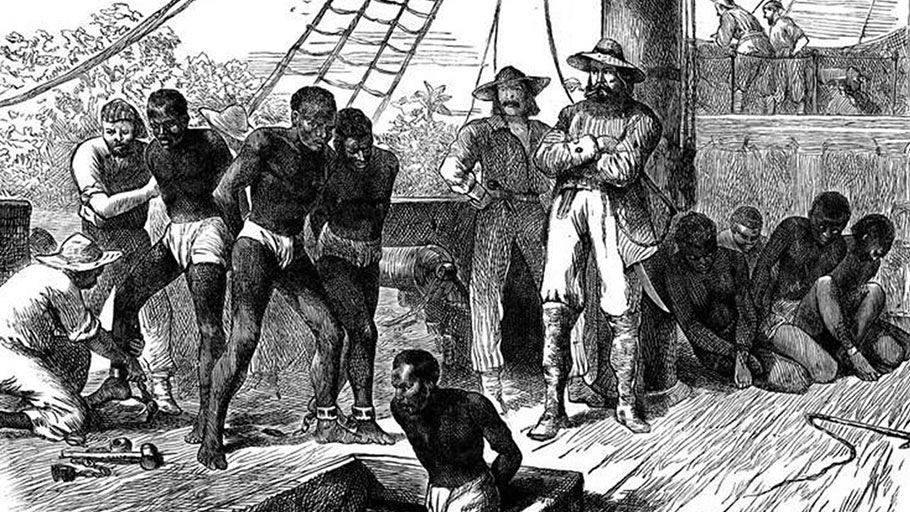

‘The Treaty,’ vintage engraved illustration. Journal des Voyage, Travel Journal, (1880-81). Photo Credit: By Morphart

The history-teaching wing of the Koch brothers empire is seeking to promote an alternate narrative to slavery

By Adam Sanchez, Zinn Education Project —

Given that the billionaire Charles Koch has poured millions of dollars into eliminating the minimum wage and paid sick leave for workers, and that in 2015 he had the gall to compare his ultra-conservative mission to the anti-slavery movement, he’s probably the last person you’d want educating young people about slavery.

Yet the history-teaching wing of the Koch brothers empire is seeking to promote an alternate narrative to slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. The political goal of these materials is to ensure students see racism and slavery as flaws in an otherwise spotless U.S. record, rather than woven into the fabric of our country from its inception.

The Bill of Rights Institute (BRI) is the education arm of the network of front groups the Koch brothers use to promote their far-right ideology. Maureen Costello, the education director from Teaching Tolerance, has pointed out the many factual inaccuracies in the “Homework Help” video the BRI has recently promoted to teach students about slavery. She concludes that the history presented is “superficial, drained of humanity, and neglects to reckon with the economic and social reality of what opponents called ‘the slave power.’”

A dive into their “Documents of Freedom” readings reveals an even more disturbing agenda. The BRI bills the “Documents of Freedom” as a “modern take on the traditional textbook” — a “completely free digital course on history, government, and economics” authored by unnamed “teachers.” It’s essentially an online textbook that aims to promote a particular version of history, government, and economics that aligns with the interests of the Kochs.

The main “Documents of Freedom” reading on slavery, titled “Slavery and the Constitution,” is essentially a defense of the founding fathers and the Constitution against “some scholars” who “portray the founding fathers as racists.” The reading cherry-picks quotes from “the Founders” to argue that they believed slavery was morally wrong. Although the authors write that “most of the signers of the Declaration and the Constitution own[ed] slaves,” they steer clear of the brutal reality of chattel slavery.

They paint Thomas Jefferson as an anti-slavery crusader who “attacked the slave trade in harsh language” and “included African Americans in the universal understanding of the promise of liberty and equality.” But the Kochs’ curriculum fails to mention that Jefferson wrote Black people were “inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” Jefferson kept nearly 200 people in bondage, and even in his death emancipated only five. He regularly sold human beings away from their families to raise money to buy wine, art, and luxuries that only wealthy planters could afford. Nothing in the BRI reading acknowledges any contradiction between “the Founders’” awareness of “the immorality of slavery and the need for action” and their actual actions defending and protecting slavery.

Furthermore, the reading justifies the so-called three-fifths compromise — whereby an enslaved person was counted as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of congressional representation — by arguing “the Founders” had to make a “prudential compromise with slavery because they sought to achieve their highest goal of a stronger Union of republican self-government. Since some slaveholding delegations threatened to walk out. . .” Not only is this type of “compromise” immoral, but the problem with this logic is that the “slaveholding delegations” that threatened to walk out were themselves “Founders” who played an important role in crafting the Constitution.

In addition to selectively quoting the founders, the authors use quotations from Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln to bolster their argument that the Constitution was an anti-slavery document. It ignores that most politicians, including Lincoln, believed that the Constitution protected slavery where it existed. It also ignores the very large wing of the abolitionist movement, whose most prominent figure was William Lloyd Garrison, that viewed the Constitution as a “devil’s pact,” one “dripping with blood.” Douglass himself was part of that wing of the movement until he broke with Garrison in the 1850s, when he became convinced that framing the Constitution as an anti-slavery document could be a useful tool in the struggle to end slavery.

The reading also ignores how central slavery was to the economic growth of the United States, with phrases like “the number of slaves steadily grew through natural increase.” Natural? There was nothing natural about the expansion of slavery. Slavery expanded because it was profitable. The authors seek to divorce the expansion of slavery from the economic design of the capitalist cotton empire and from the horrific practice of breeding, which became a large source of revenue, especially for Virginia slaveholders.

What is most egregious is what the reading leaves out. Even today’s corporate textbooks will include a paragraph or two that attempt to provide the perspective of enslaved people. However, this reading concludes by arguing there was a steady “rise of freedom” after the Constitution because “the new nation was mostly bent on expanding liberty and equality.” The only way the Koch brothers’ Bill of Rights Institute can draw this conclusion is by completely ignoring the perspective of those whose land and labor were violently stolen by the wealthy U.S. elite.

As if that reading wasn’t bad enough, the follow-up reading, titled “Civil War and Reconstruction,” is a long, boring account that almost exclusively focuses on the battles between Radical Republicans in Congress, who the authors claim wanted to “punish the South,” and Presidents Lincoln and Johnson, who favored more “moderate” reconstruction plans. It might be the first reading I’ve ever looked at on Reconstruction that makes almost no mention of what Black people were doing during the era and barely discusses anything happening in the South.

Only in a pro-KKK film like Birth of a Nation and in the Koch brothers’ curriculum is Reconstruction reduced to a punishment for white Southerners. Let’s look at Reconstruction from the standpoint of those who were freed from more than 200 years of enslavement. It was a time when the formerly enslaved became congressmen; when the Black-majority South Carolina legislature taxed the rich to pay for public schools; when experiments in Black self-rule in the Georgia Sea Islands led to land reform, new schools, and a vital local governance. During Reconstruction Blacks and poor whites organized Union Leagues, and led strikes, boycotts, demonstrations, and educational campaigns. During this period other social movements, especially labor and feminist movements, were inspired by the actions of African Americans to secure and define their own freedom.

As the late historian Lerone Bennett Jr. wrote: “It had never happened before, and it has never happened since, in America.” During Reconstruction, “the poor, the downtrodden, and the disinherited present[ed] their bills at the bar of history.” Of course, today’s elites like the Kochs have no interest in students learning this radical history. In the Kochs’ history, the only mention of Black people’s actions comes in one sentence at the end of the reading that papers over the massive accomplishments of the era: “Although African Americans soon made up the majority of voters in some southern states and even elected some black representatives to Congress, the right to vote was curtailed by southern states through several legal devices. . .”

Tellingly, the Koch authors finish off this reading with a quote from James Madison about the “Tyranny of Majorities.” The authors claim that Jim Crow was an example of when “African Americans in the post-Civil War South discovered firsthand the dangers of majority tyranny in a republic.” That’s the main lesson the Bill of Rights Institute wants students to draw from the Civil War and Reconstruction: You can’t trust the masses, so leave politics to elites like the Koch brothers. Of course, the inconvenient truth is that when one actually focuses on the South during Reconstruction, we see an era where poor white and Black people took political power away from elites. It’s this history that the Koch brothers don’t want students to learn.