The Virginia Theological Seminary is giving cash to descendants of Black Americans who were forced to work there. The program is among the first of its kind.

By Will Wright, The New York Times

One night in 1858, Carter Dowling, an enslaved Black man forced to work without pay at the Virginia Theological Seminary in Northern Virginia, made the brave decision to escape.

He made it to Philadelphia, where he met the famed abolitionist William Still. He then continued north to Canada and, after the Civil War, returned to Washington, D.C., where he was able to open a bank account for his children. He eventually went on to work as a labor organizer in Buffalo.

To this day, Mr. Dowling’s family line continues. And, most likely for one of the first times in American history, his descendants could receive cash payments for his forced labor.

In February, the Virginia Theological Seminary began handing out cash payments to the descendants of Black Americans who were forced to work there during the time of slavery and Jim Crow.

The program is among the first of its kind. Though other institutions have created atonement programs, such as scholarships and housing vouchers for Black people, few, if any, have provided cash. (The Times could not verify whether the seminary is the first to provide cash payments.)

“When white institutions have to face up with the sins of their past, we’ll do everything we can to prevaricate, and we’ll especially prevaricate if it’s going to have some sort of financial implication,” said the Rev. Ian S. Markham, the president and dean of the seminary, which is in Alexandria, Va. “We wanted to make sure that we both not just say and articulate and speak what’s right, but also take some action — and we were committed to that from the outset.”

Ian Markham, president and dean of Virginia Theological Seminary in 2019. Credit: Justin T. Gellerson for The New York Times

The checks, about $2,100 this year, will come annually and have begun to flow to the descendants of those Black workers. The money has been pulled from a $1.7 million fund, which is set to grow at the rate of the seminary’s large endowment. Though just 15 people have received payments so far, that number could grow by the dozens as genealogists pore through records to find living descendants.

The program authorized payments to the members of the generation closest to the original workers, calling them “shareholders.” If that generation includes people who have died, the payments would go to their children. And if that person had no children, the money would be split among the siblings of the eldest generation.

The Rev. Joseph Thompson, the seminary’s director of multicultural ministries, remembers the day that Mr. Markham walked into his office and asked what he thought about creating a reparations program.

“This is one of those things I never thought I would see in my lifetime — a serious, a kind of broad conversation about reparations in the United States of America,” he said. “That was a very striking moment for me.”

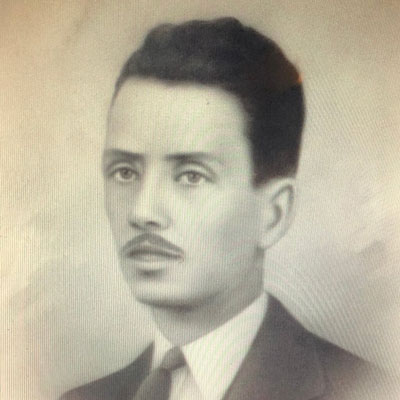

John Samuel Thomas Jr., worked at the seminary after World War I as a janitor, and most likely also as a laborer on the seminary’s farm. His granddaughter, Linda J. Thomas, was the first woman to receive a $2,100 payment from the seminary.

The seminary’s leaders acknowledge that the particulars of who will receive money, and how much, could be complicated. Take the case of Mr. Dowling. While he was Black, his grandchildren identified themselves on official records as white, and so have their descendants.

Maddy McCoy, a genealogist working with the seminary to find the descendants of enslaved individuals, said that while such situations have presented difficult questions, the seminary had tackled them head on.

“There is no manual that we are referring to as we move through this,” Ms. McCoy said. “With that, it’s going to be a lot of ups and downs and a lot of really, really difficult decisions and difficult conversations, but that’s what this work is.”

The expansion of the program in the coming years will coincide with the seminary’s 200th anniversary in 2023. The seminary, a 25-minute drive south from Washington, has become the most powerful in the Episcopal Church. It graduates about 50 students a year and boasts a $191 million endowment.

But the institution, for all its prominence, depended for decades on the labor of Black people who were never paid adequately for their labor — or were never paid at all. They included gardeners, cooks, janitors, dishwashers and laundry workers. The exact number of Black workers from 1823 to 1951 is still unknown, but they probably numbered in the hundreds.

Among them was the grandfather of Linda J. Thomas, the first woman to receive a $2,100 payment from the seminary. Ms. Thomas’s grandfather, John Samuel Thomas Jr., worked at the seminary after World War I as a janitor, and most likely also as a laborer on the seminary’s farm.

Linda Thomas is the granddaughter of John Samuel Thomas Jr. Though the payments are modest, she said she hoped the program would mark a shift in the American narrative around reparations — both about the exploitation of Black people and the institutions that benefited. Credit: Kenny Holston for The New York Times

Ms. Thomas, 65, said her mother remembered growing up in a little white house on the campus. She said her grandfather had dreamed of becoming a minister but had been barred from applying to the seminary because of his skin color. Eventually, near the end of World War II, he moved to Washington and became a minister before his death in 1967.

Though the payments are modest, she said she hoped the program would mark a shift in the American narrative around reparations — both about the exploitation of Black people and the institutions that benefited. “For so many years, people with the sweat on their backs not only picked cotton, but built institutions,” she said.

While the seminary’s program is groundbreaking in the United States, William A. Darity, a professor of public policy and African-American studies at Duke University, said such atonement programs should not be interpreted as sufficient in righting the wrongs of slavery or in eliminating the effects of racist policies.

The only institution that can fund a comprehensive reparations program large enough to atone for the lost wages of slavery or bridge the racial wealth gap is the federal government, he said. “This is not a matter of personal guilt,” he added, estimating that such a comprehensive program would require $11 trillion. “This is a matter of national responsibility.”

Public support for reparations has grown over the years, from 19 percent of those surveyed in 1999 to 31 percent in 2021, according to polls from ABC and The Washington Post. But even within the seminary, the atonement program drew some pushback.

Mr. Markham said a handful of donors had objected and had said they would no longer contribute money. They also heard from some people who asked to be removed from the seminary’s mailing lists.

In determining how to provide reparations, a common dividing line has been whether to provide cash. The City Council of Evanston, Ill., agreed to distribute $10 million to Black families in the form of housing grants, though the particulars of that plan remain unclear. Earlier this year, Gov. Ralph Northam of Virginia signed a law requiring five public universities to create scholarships and community development programs for Black individuals. And in March, a prominent order of Catholic priests vowed to raise $100 million to benefit the descendants of the enslaved people it once owned.

The Rev. Ian S. Markham, right, gives Gerald Wanzer a tour of the seminary campus in March. Mr. Wanzer, one of the shareholders, said the records examined by the seminary had revealed new details about several members of his family who worked there. Credit: Kenny Holston for The New York Times

Payments are a fundamental part of the Virginia seminary’s program, said Ebonee Davis, the associate for multicultural ministries, but she added that relationships with families, as well as the recognition of their ancestors’ contributions, were also crucial. “I’ve cried on the phone with shareholders,” she said. “We’ve laughed and kind of shared our disbelief that this is actually happening.”

It is no small task to confirm the identities of enslaved people who worked at the seminary, along with their descendants. It is likely that from 1823 to 1865, at least 290 people labored there, according to the research staff. From 1865 to 1951, there were probably hundreds more.

Gerald Wanzer, one of the shareholders, said the records examined by the seminary had revealed new details about several members of his family who worked there as general laborers, laundresses and janitors. His great-grandfather, a blacksmith, is believed to have been the first.

But Mr. Wanzer, 77, said that the seminary “can never make up for what happened 150 years ago, and the money is not going to change, personally, my views.” Mr. Wanzer said that in his own lifetime, he had experienced much of the racism that his ancestors endured.

“I never had to ride in the back of the bus, but I do remember the separate bathrooms and the separate water foundations, and not being able to get served at the carry-outs,” he said, adding that those experiences had fueled his belief that he would never live to see atonement in the form of cash payments.

Gerald Wanzer at the seminary in March. Credit: Kenny Holston for The New York Times

Mr. Markham said that he believed America was facing a reckoning over racial inequality and that the seminary’s program, though modest, would help nudge the nation away from its tendency to turn a blind eye.

“I think the time has come to say, ‘No, you can’t anymore,’” he said. “You actually do need to really face up to what happened, how it happened, and how you make it right.”

Source: The New York Times

Featured Image: The Virginia Theological Seminary, in Alexandria, Va., in February began handing out cash payments to the descendants of Black Americans who labored there during the time of slavery and Jim Crow. Credit: Kenny Holston for The New York Times