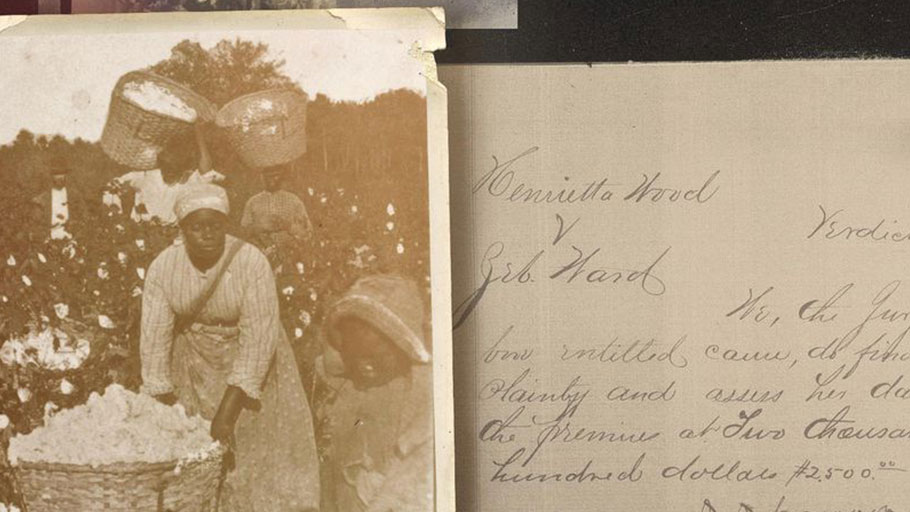

No image of Henrietta Wood survives today, but her story is recorded in court filings, including the verdict slip above. (Illustration by Cliff Alejandro; Source material: W. Caleb McDaniel; NYPL (3))

In 1870, Henrietta Wood Sued for Reparations—and Won. The $2,500 verdict, the largest ever of its kind, offers evidence of the generational impact such awards can have.

On April 17, 1878, 12 white jurors entered a federal courtroom in Cincinnati to deliver the verdict in a now-forgotten lawsuit about American slavery. The plaintiff was Henrietta Wood, described by a reporter at the time as “a spectacled negro woman, apparently 60 years old.” The defendant was Zebulon Ward, a white man who had enslaved Wood 25 years before. She was suing him for $20,000 in reparations.

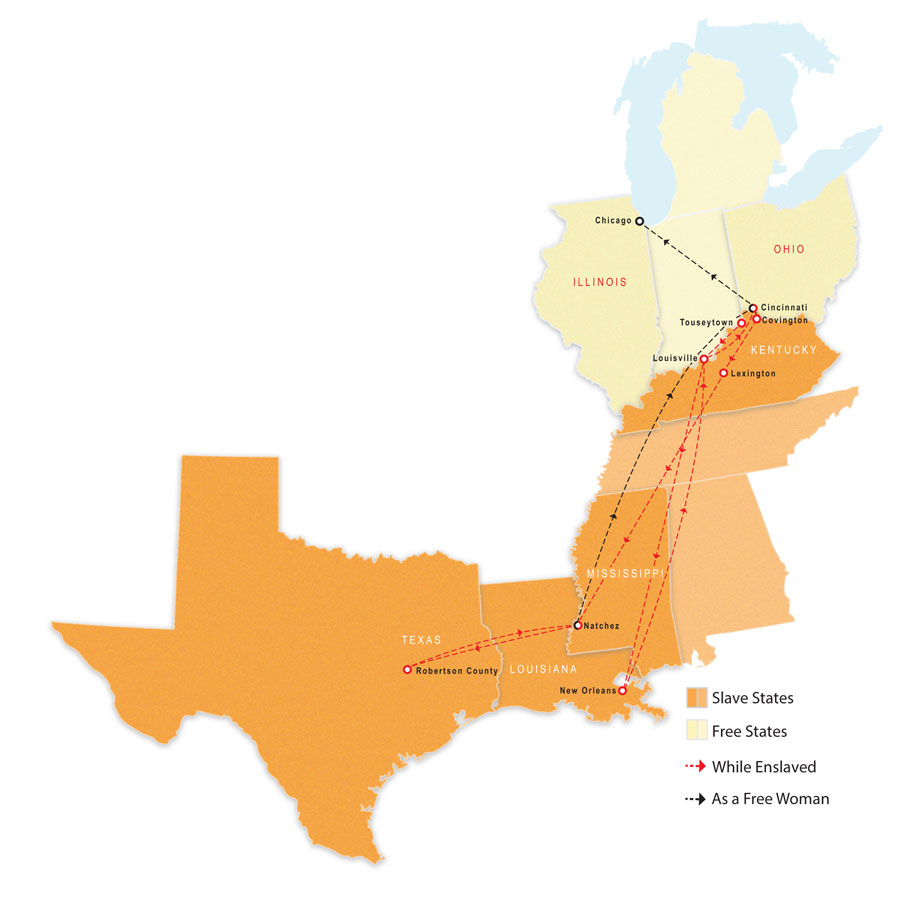

Two days earlier, the jury had watched as Wood took the stand; her son, Arthur, who lived in Chicago, was in the courtroom. Born into bondage in Kentucky, Wood testified, she had been granted her freedom in Cincinnati in 1848, but five years later she was kidnapped by Ward, who sold her, and she ended up enslaved on a Texas plantation until after the Civil War. She finally returned to Cincinnati in 1869, a free woman. She had not forgotten Ward and sued him the following year.

The trial began only after eight years of litigation, leaving Wood to wonder if she would ever get justice. Now she watched nervously as the 12 jurors returned to their seats. Finally, they announced a verdict that few expected: “We, the Jury in the above entitled cause, do find for the plaintiff and assess her damages in the premises at Two thousand five hundred dollars.”

Though a fraction of what Wood had asked for, the amount would be worth nearly $65,000 today. It remains the largest known sum ever granted by a U.S. court in restitution for slavery.

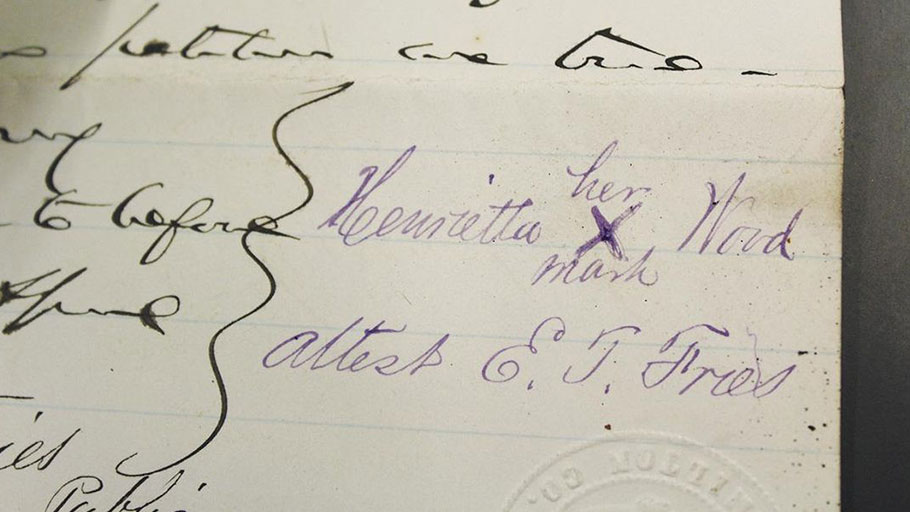

Wood’s mark on an affidavit from Wood v. Ward. (W. Caleb McDaniel)

But Wood’s name never made it into the history books. When she died in 1912, her suit was already forgotten by all except her son. Today, it remains virtually unknown, even as reparations for slavery are once again in the headlines.

I first learned of Wood from two interviews she gave to reporters in the 1870s. They led me to archives in nine states in search of her story, which I tell in full for the first time in my new book, Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America.

***

Henrietta Wood’s story began two centuries ago with her birth in northern Kentucky.

“I can’t quite tell my age,” Wood recalled in a newspaper interview in 1876, but she knew she was born enslaved to the Tousey family between 1818 and 1820. In 1834, the teenager was bought by a merchant in Louisville and taken from her family. She was soon sold again, to a French immigrant, William Cirode, who took her to New Orleans.

Cirode returned to France in 1844, abandoning his wife, Jane, who eventually took Wood with her to Ohio, a free state. Then, in 1848, Jane Cirode went to a county courthouse and registered Wood as free. “My mistress gave me my freedom,” Wood later said, “and my papers were recorded.” Wood spent the next several years performing domestic work around Cincinnati. She would one day recall that period of her life as a “sweet taste of liberty.”

All the while, however, there were people conspiring to take her freedom away. Cirode’s daughter and son-in-law, Josephine and Robert White, still lived in Kentucky and disagreed with Jane Cirode’s manumission of Wood; they viewed her as their inheritance. By the 1850s, the interstate slave trade was booming, and the Whites saw dollar signs whenever they thought of Wood. All they needed was someone to do the dirty work of enslaving her again.

Brandon Hall, where Wood toiled as a slave in the 1850s, as it looked in 1936. (Library of Congress )

Zebulon Ward was their man. A native Kentuckian who had recently moved to Covington, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, Ward became a deputy sheriff in 1853. The Whites lived in Covington, too, and in the spring of 1853 they persuaded Ward to pay them $300 for the right to sell Wood and pocket the proceeds himself — provided he could get her.

Gangs worked throughout the antebellum period to capture free black men, women, and children and smuggle them into the South, under the cover of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which required the return of runaway slaves. Ward began to plot with a group of these notorious “slave catchers.” The gang located Wood’s employer in Cincinnati, a boardinghouse keeper named Rebecca Boyd, and paid her to join their scheme. One Sunday afternoon in April 1853, Boyd tricked Wood into taking a carriage ride across the river. And when the carriage finally rolled to a stop outside of Covington, Ward’s men were waiting.

It would be 16 years before Wood set foot in Ohio again.

She spent the first nights of her captivity locked inside two roadside inns. Her captors’ destination was Lexington, Kentucky, where prices for slaves had risen with the Southern cotton economy. After 1815, as white settlers rushed into the lower Mississippi River Valley, many looked to purchase slaves to cultivate the region’s most profitable crop. Slave traders met the demand by buying slaves in Virginia, Kentucky, and Maryland and selling them in the cotton states. Between 1820 and 1860, nearly a million people were sold “down the river.”

Ward planned to make Wood the latest victim of this trade, but she resolved to fight. Wood secretly told her story to a sympathetic innkeeper who followed her to Lexington, where a lawsuit was filed on her behalf asserting that she was free. Wood was never allowed to testify, however, and Ward denied her claims. Her official freedom papers, at a courthouse in Cincinnati, had been destroyed in an 1849 fire, and her kidnappers had confiscated her personal copy. The case was eventually dismissed. In the eyes of Kentucky law, Wood was a slave.

The freedom suit had prevented Ward from selling Wood for nearly two years, but in 1855, he took her to a Kentucky slave-trading firm that did business in Natchez, Mississippi. The traders put Wood up for sale at Natchez’s infamous Forks of the Road slave market. Gerard Brandon, one of the largest slaveholders in the South, bought Wood and took her to his house, Brandon Hall, on the Natchez Trace. “Brandon was a very rich man,” Wood later said. He owned 700 to 800 slaves on several plantations, and he “put me to work at once in the cotton field,” she said. “I sowed the cotton, hoed the cotton, and picked the cotton. I worked under the meanest overseers, and got flogged and flogged, until I thought I should die.”

At some point during those hellish days, Wood gave birth to Arthur, whose father is unknown. She was later removed from the cotton fields and put to work in Brandon’s house.

The Civil War began, followed in 1863 by the Emancipation Proclamation, but Wood’s ordeal continued. On July 1, 1863, just days before the U.S. Army arrived to free thousands of people around Natchez, Brandon, determined to defy emancipation, forced some 300 slaves to march 400 miles to Texas, far beyond the reach of federal soldiers. Wood was among them. Brandon kept her enslaved on a cotton plantation until well after the war. Even “Juneteenth,” the day in June 1865 when Union soldiers arrived in Texas to enforce emancipation, did not liberate Wood. It wasn’t until she returned to Mississippi with Brandon in 1866 that she gained her freedom; she continued to work for Brandon, now promised a salary of $10 a month, but she would say she was never paid.

It was four years after the Confederate surrender before Wood was able to return up the river, where she tried to locate long-lost members of her family in Kentucky. Whether she succeeded in that quest is unknown — but she did find a lawyer, Harvey Myers. He helped Wood file a lawsuit in Cincinnati against Ward, now a wealthy man living in Lexington. The postwar constitutional amendments that abolished slavery and extended national citizenship to ex-slaves enabled Wood to pursue Ward in federal court.

Ward’s lawyers stalled, claiming that Wood’s failed antebellum suit for freedom proved his innocence. They also said that Ward’s alleged crimes had occurred too far in the past — a recurring argument against reparations. Wood suffered another, unexpected setback in 1874, when her lawyer was murdered by a client’s husband in an unrelated divorce case. Then, in 1878, jurors ruled that Ward should pay Wood for her enslavement.

A record now at the National Archives in Chicago confirms that he did, in 1879.

***

Wood’s victory briefly made her lawsuit national news. Not everyone agreed with the verdict, but the facts of her horrific story were widely accepted as credible. The New York Times observed, “Files of newspapers of the five years following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law are filled with stories of the kidnapping of free men in free States.” (In fact, free black Northerners had been kidnapped for years before the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.) Some newspapers even predicted that lawsuits like hers would proliferate. As one put it, Wood’s award was “not a liberal equivalent for the loss of liberty” she had suffered, but it would “be applicable to a great many cases yet untried.”

Yet Wood v. Ward did not set a sweeping legal precedent. Even the judge who presided over Wood’s case, Phillip Swing, viewed it narrowly. “Fortunately for this country the institution of slavery has passed away,” he had instructed the jurors, “and we should not bring our particular ideas of the legality or morality of an institution of that character into Court or the jury-box.” He had cautioned the jurors against an excessive award, claiming — falsely — that many former slaveholders already regretted slavery.

Map traces Henrietta Wood’s tortuous path from slavery to freedom—and back

Swing also told the jurors to focus on Wood’s kidnapping in assessing the case, and the vast majority of freed people could not show, as Wood did, that they had been re-enslaved. But Wood and her lawyers had argued that the case was about much more than damages from abduction. By suing Ward for the wages she had lost while owned by Brandon, her lawyers made clear that a verdict for Wood was an acknowledgment of the evils of slavery itself.

Few white Americans wished to dwell on those evils. By 1878, white Northerners were retreating from Reconstruction. Newspapers described Wood’s suit as an “old case” or a “relic of slavery times,” consigning stories like hers to a fading past. “Not so many complications of a legal nature arise out of the old relations of master and slave as might have been expected,” the New-York Tribune argued with barely concealed relief.

Arthur H. Simms, Wood’s son, photographed in 1883 or 1884, at about age 27. (David M. Blackman)

Wood was an early contributor to a long tradition of formerly enslaved people and their descendants demanding redress. In the 1890s another formerly enslaved woman, Callie House, led a national organization pressuring the government for ex-slave pensions. In 1969, civil rights leader James Forman issued a manifesto calling on churches and synagogues to pay half a billion dollars in reparations to black Americans. Today, many reparations advocates look to legislation, targeting governments for their complicity in slavery and white supremacy. They note that disenfranchisement and segregation only worsened the racial wealth gap, which was established under slavery and remains today. While Wood received $2,500 as compensation for more than 16 years of unpaid labor, her former enslaver, Ward, left an estate worth at least $600,000 when he died in 1894, a multimillionaire in today’s terms.

But Wood’s award, however insufficient, was not ineffectual. After her suit, she moved with her son to Chicago. With help from his mother’s court-ordered compensation, Arthur bought a house, started a family, and paid for his own schooling. In 1889, he was one of the first African-American graduates of what became Northwestern University’s School of Law. When he died in 1951, after a long career as a lawyer, he left behind a large clan of descendants who were able to launch professional careers of their own, even as redlining and other racially discriminatory practices put a chokehold on the South Side neighborhoods where they lived. For them, the money Henrietta Wood demanded for her enslavement made a long-lasting difference.

This article was originally published by Smithsonian Magazine.