Watchmen takes place in Tulsa, OK, home of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. — Mark Hill, HBO.

The perils facing Blacks in Tulsa, Oklahoma didn’t end with the show’s season finale.

Watchmen may have been snubbed by the Golden Globes, but the season finale left many viewers in awe. As Black women who hail from Tulsa, Oklahoma — where the Watchmen plot plays out — we hope the season’s biggest legacy will be what it forces all of us to consider now that it’s over. This is not the time for white Americans to pat themselves on the back for caring about fictional Black characters. It’s time to discuss how to do right by real Black communities that must continue to face off with white supremacy after the episodes end.

In other words, it’s time to discuss reparations for descendants of enslaved people and victims of racial violence in America.

Viewer reaction to the show’s opening moments demonstrated why this conversation, and a reckoning with U.S. history, is desperately needed. Scenes of murderous terror by white mobs in the streets of the Greenwood District in North Tulsa, Oklahoma’s most prosperous Black community captivated the eyes of millions in Watchmen’s premiere episode. This reenactment of real events in 1921 introduced many viewers to one of the most devastating racial massacres in U.S. history and left them shocked at their proximity to such horror.

Scene from Watchmen

Reenactment of the “Tulsa race massacre” of 1921

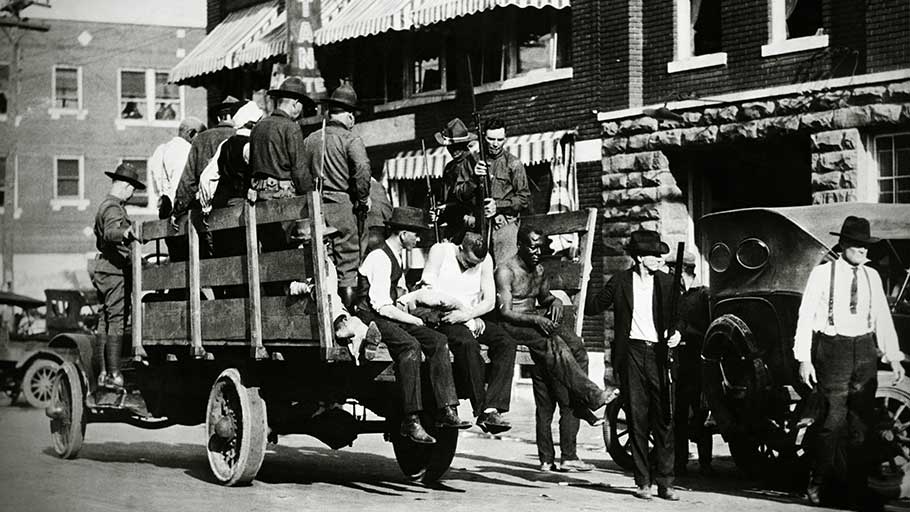

Actual Photos

The “Tulsa race massacre” of 1921 spanned two days when mobs of white rioters attacked local black residents and businesses in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. — Oklahoma Historical Society.

- A Black man with a camera looks at the skeletons of iron beds which rise above the ashes of a burned-out block after the massacre in June 1921.

Months after its airing, the bloody scene is still understandably hard to shake. But it’s even worse for the Black Americans who continue to reel from the intergenerational toll such carnage has taken. One of this op-ed’s authors is the great niece of a woman who barely escaped a Greenwood theatre when the massacre broke out.

After the depiction of the massacre, it comes into view that much of Watchmen is an alternate universe, one where police are supposedly a force against white supremacy and must call into dispatch before drawing their weapons. It’s a thought-provoking reversal of America’s off-screen reality. The U.S. has a long and ongoing history of law enforcement protecting and actively participating in white supremacist groups and extremism. In real life, police, often operating on a “shoot first” basis, disproportionately kill Black people as compared to their white peers. In fact, a recent study found that about 1 in 1,000 Black men and boys in America can expect to die at the hands of police — a rate that makes them 2.5 times more likely than white men and boys to die during a police encounter.

What rings truest in this TV series and in America today is the need to examine what reparations look like for generations of trauma and losses. But how?

Does it look like the short-lived promise of “40 acres and a mule,” or equal access to housing and land acquisition? Does it look like block grants for community-oriented businesses? Does it look like a lifetime of free trauma-informed care?

Regina King as Detective Angela Abar, aka Sister Knight.

In Watchmen, the government at least attempted to find an answer. In the show, “Redfordations” are a byproduct of the “Victims of Racial Violence Act.” Writer-producer Damon Lindelof describes such amends as “a lifetime tax exemption for victims of, and the direct descendants of, designated areas of racial injustice throughout America’s history.” Regina King plays Detective Angela Abar, aka Sister Knight — a lead character and beneficiary of the policy, as some members of her family were murdered in the Tulsa massacre.

In real life, Black Tulsans were denied reparations by their own state legislature even after the 1997 Tulsa Race Riot Commission recommended the state pay $33 million in restitution to surviving victims. Etched in black marble at the Black Wall Street Memorial in Tulsa, sources indicate the only known payments of restitution were for guns and ammunition to white assailants — not the devastation of economic prosperity and lives lost. Tulsa historian Dr. Alicia Odewale estimates property damages to be in the range of $50–100 million in today’s dollars.

The history of Tulsa’s race massacre is only buried to some. For many Black Tulsans, they continue to live through the legacy of white supremacy in the form of biased policing and other inequities discussed in a recent report by Human Rights Watch.

The report shows that Black Tulsans have a lower life expectancy than their white counterparts and are relegated to poverty at higher rates. They experience everyday police abuse and disparities in treatment by police, including being subject to arrest at a rate 2.3 times greater, cited for traffic violations 1.4 times more frequently and subjected to stops of a longer duration, than white people. Inequities extend beyond police enforcement and into the criminal legal system where oppressive amounts of court debt trap Black and poor Tulsans in a cycle of inescapable poverty. Such systemic discrimination is replicated in health, housing, education and employment across the nation.

Some real-life lawmakers are trying to explore how to rectify these intergenerational harms. H.R. 40 was first brought to the floor by former U.S. Congressman John Conyers in 1989 and then reintroduced every year until his retirement in 2017, with no voting actions ever taken. Fortunately, it was reintroduced by U.S. Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee in January 2019 but has not been voted out of committee. This bill calls for a commission to study the impacts of slavery and racial discrimination and to make recommendations around remedies and compensation. These would be important steps towards justice in a way that this nation has avoided for centuries.

In the United States, much of the debate on reparations boils down to whom we deem worthy recipients of redress, justice and reconciliation. Black people are worthy. And we shouldn’t have to turn into DC superheroes to prove it.

This article was originally published by Blavity.

Kristi Williams is a longtime resident of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Greenwood advocate and tour guide with the Real Black Wall Street Tour Company

Dreisen Heath was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma and is an advocacy officer for the US Program at Human Rights Watch