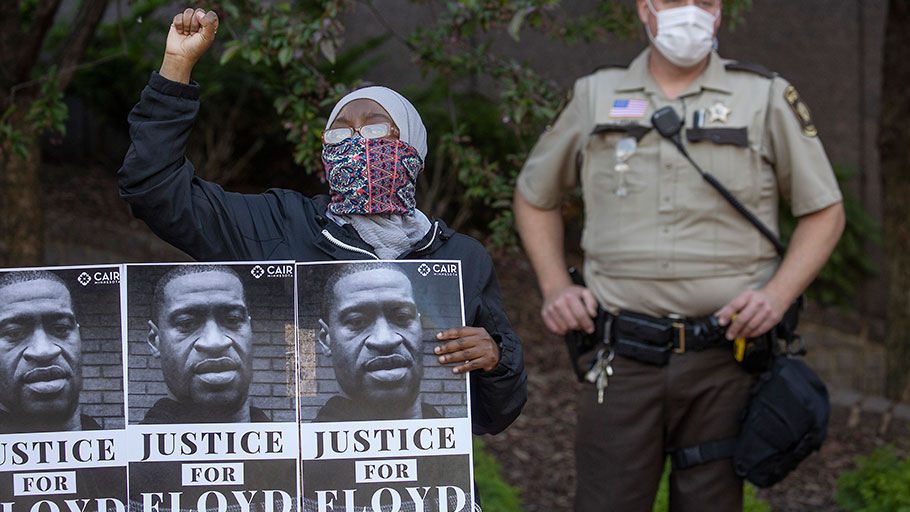

A protester in Minneapolis on Thursday. Photo by Elizabeth Flores, Minneapolis Star Tribune, AP

By Peniel E. Joseph, The Washington Post —

The police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the subsequent protests, which featured law enforcement tear-gassing demonstrators, highlight the urgent need to transform America’s criminal justice system. Floyd, 46, managed to outrun the coronavirus pandemic that has taken too many black lives, only to be ensnared by that quintessentially American and dangerously malignant virus of white supremacy.

In a video capture eerily reminiscent of the death of Eric Garner, the black man killed by New York police while pleading “I can’t breathe” in 2014, Floyd’s arrest, for allegedly trying to pass a counterfeit $20 bill, turned into a public execution. Footage of a white officer jamming his knee against Floyd’s neck has gone viral, sparking real-life and social media outrage that recalls the hashtag activism that inspired the Black Lives Matter movement.

Black Lives Matter combined civil rights-era disobedience with Black Power’s structural critique of white-supremacist America’s historic use of violence against black bodies. The movement turned white-supremacist logic on its head by proclaiming the humanity of black people, spawning repudiation from police unions who smeared the group as black terrorists and white liberals, and conservatives whose “all lives matter” retort only exposed the depth and breadth of their deep-seated racism, privilege and ignorance.

Black death at the hands of the police is not new. The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, Calif., in 1966, in part to combat police brutality witnessed and experienced by its founders, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. The BPP brandished legally owned weapons and law books in a quest to defend the black community and observe law enforcement from a legally permitted distance.

The Panthers published the first issue of the Black Panther newspaper in 1967 in response to the police killing of a black man, Denzil Dowell, in nearby Richmond, Calif. In May of that year, the BPP famously sent a group of 30 armed Panthers to the Sacramento legislature to protest a gun-control bill, which eventually passed, designed expressly to prevent black people from lawfully carrying guns while observing the police. The Panthers’ expansive efforts to defend black lives included scores of community programs, health clinics, legal aid and breakfast for children, but their lasting image in popular culture remains linked to their courageous — critics labeled them reckless — efforts to end police violence.

Police brutality and killings of unarmed black men, women, girls and boys have continued in our era, long after the Panthers’ heyday. Instructively, the Panthers characterized America’s justice system as a boldface lie, one linked to the economic exploitation and racial impoverishment of black communities.

During the Reconstruction era, the convict-lease system arrested black men and women for vagrancy, worked many of them to death, and exploited their labor in service of private capital and public infrastructure. In the aftermath of Michael Brown’s 2014 death at the hands of a Ferguson, Mo., police officer, a Justice Department report revealed that black residents there were victims of a law enforcement scheme that levied fines, warrants and fees against the community as a way to generate revenue.

America’s criminal justice system is based on extraordinary and systemic lies about protecting white lives, property, the sanctity of white womanhood and the safety of white neighborhoods. Evidence of the profundity of these white lies surrounds us, from the exonerations of the Central Park Five, the teenage black and Latino boys wrongly accused of rape, to innocence projects that doggedly pursue justice for the few while hundreds of thousands more languish in prison.

Movements to end police brutality continued at the local level between the Panthers and the rise of Black Lives Matter but were often overwhelmed by the structural power and cultural hysteria of the war on drugs that criminalized black neighborhoods and residents. The “law and order” rhetoric innovated by President Richard Nixon captured both major parties by the 1990s.

The crime bills and zero-tolerance policies touted by Democrats and Republicans — including former vice president and presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden — during the drug wars of the ’80s and ’90s amplified the metaphorical noose around the entire black community.

Black frustration with police seemingly being granted immunity for an endless array of unjustified force, violence and death against defenseless African American communities has elicited spasms of grief, outrage and anger across the nation. Violence that has contoured protests in Minneapolis, Ferguson and Baltimore is the language of black communities racially and economically oppressed for decades.

Black punishment, trauma, dehumanization and death are not preordained. Contemporary movements to end mass incarceration often focus on the need for more education, jobs, social workers, drug rehabilitation and mental-health care, and fewer cops. Black communities too often remain overpoliced and under-resourced. In this way, George Floyd’s death is the culmination of thousands of policy choices this nation continues to make that result in premature black death.

Past freedom movements offer hope and caution. Civil rights-era struggles to end racial segregation in public schools and neighborhoods and secure voting rights proved more successful than originally conceived. Despite the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, America’s schools remain entrenched in racial segregation, a phenomenon that courts have given up on remedying. Black voting power flexed enough muscle to help elect Barack Obama president twice, before the 2013 Shelby v. Holder Supreme Court decision effectively curtailed federal oversight of the Voting Rights Act and ushered in a mean, ongoing season of voter suppression. For every policy step toward black dignity and citizenship that black folk have won, there have been counterrevolutions that have stymied the depth and breadth of the progress we hoped to achieve.

Yet this should not deter the impulse for radical social transformation in our own era. The movement for black lives, despite making fewer headlines in recent years, has helped to spur the election of reform-minded district attorneys around the country, and inroads into ending the racist bail system have been hard won. Change in our lifetime is possible, however painstaking and inadequate. George Floyd’s memory offers more heartbreaking inspiration to finally achieve the dignity and citizenship that remain the beating heart of the black freedom struggle.

Source: The Washington Post

Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He also is the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. His latest book is”The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.”