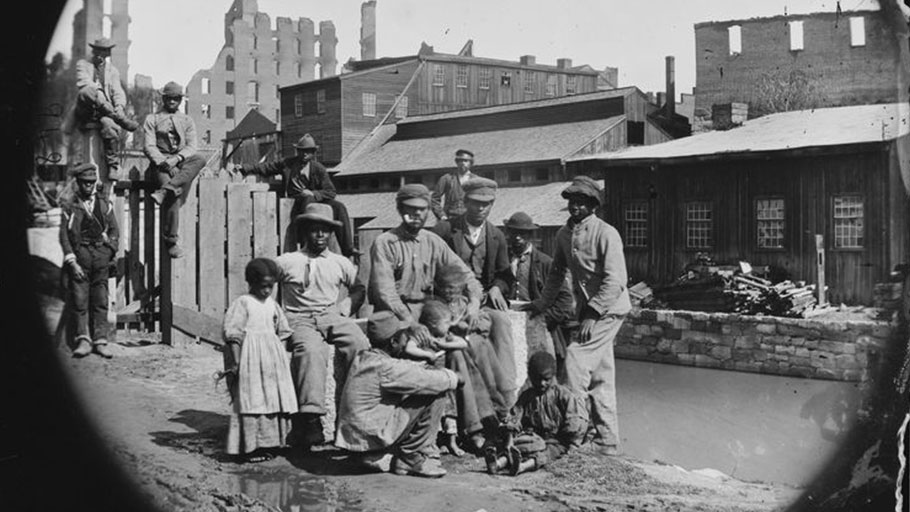

In a photo from the Library of Congress, free men, women, and children in Richmond, Va., 1865. In 1865, formerly enslaved people were promised 40 acres of land and, later, a mule. More than 150 years since then, some politicians are trying to make good on a version of that promise through reparations. Library of Congress/NYT

The legacy of slavery is far from resolved. It persists every day and everywhere.

By David Gardinier and Karen Hilfman, The Boston Globe —

Since the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by a white police officer, and the resounding anti-racist uprisings around the world, the concept of reparations has picked up momentum in national conversations and has sparked new public curiosity and interest. Among Black people and their ancestors, however, reparations for slavery have been on their hearts and minds for a very long time.

True Black history, which few white people — including us — learned in school, points to numerous calls for reparations for Black Americans, such as efforts centered on the passage of bills in Congress.

In 1989, the late Representative John Conyers of Michigan introduced a bill calling for a commission to study reparations for the first time, and again in every subsequent legislative session until he retired, in 2018. The current bill was introduced in the House by Representative Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas and has 143 cosponsors. It would establish a commission to examine slavery and discrimination from colonial times through the present and “recommend appropriate remedies.” For the first time, a companion bill was introduced in the Senate, championed by Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey.

In 2014, the call for reparations was brought into wider public circulation when The Atlantic published Ta-Nehisi Coates’s seminal article “The Case for Reparations.” In this influential piece, Coates deftly and exquisitely lays bare, for a predominantly white, liberal audience, how America’s enslavement of Black people resulted in structures intended to create systemic racial disparities in housing, wages, lending, voting, and more. A debt is owed.

Even after all these years and excruciating efforts, our country still has never managed to atone for the brutal devastation that began in 1619, when enslaved Africans were brought to Jamestown, Va.

The legacy of slavery is far from resolved. It persists every day and everywhere, as evidenced by income and wealth inequality, disparate living conditions and health outcomes, police brutality and mass incarceration, and the overall white supremacist system that treats white and Black lives in vastly different ways.

The other side of this history, the part that was rarely told, is that the wealth generated from all that “free” enslaved labor, combined with the theft of land from indigenous peoples, is what placed white Americans solidly among the wealthiest people on earth today.

That truth was laid bare in a 2016 book by 16 scholars, “Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development,” which names slavery as the bedrock of the American economic system. Though we whites alive today didn’t do the dirty work it took to create this wealth and privilege based on skin color, we live with the consequences of it. And those consequences go much deeper than we often realize.

What follows next in this American story of theft, murder, and profound mistreatment of Black people, and the ongoing legacy of slavery, is up to all of us. We’ve had 400 years of opportunity to make amends and set things right, and Black people have endured 400 years of waiting for America to do just that.

As Americans who long for a more enlightened narrative on race than the one we’ve had so far, we formed a collective with like-minded white people called the Fund for Reparations NOW!, which works in solidarity with the National African American Reparations Commission.

Following the Black leadership of NAARC, our fund is a nonprofit philanthropic venture seeking to further the racial healing of America through the expedited implementation of NAARC’s 10-point reparations plan. The Fund is designed to model what reparations could look like through the 10-point plan once formal reparations are legislated by the US government.

Our ultimate goal is to see the federal government formally apologize and pay reparations to Black people. It’s time for members of Congress to hear from white people too and urge lawmakers to support reparations. Until legislation passes, we have committed to doing what our white ancestors never did: Acknowledge the deep violations committed and pay reparations for those violations. We have no illusions that apologizing will fully mitigate the offenses this country has committed, or that any amount of money could compensate for the unconscionable loss of human life, rights, opportunity, justice, and freedom Black Americans have experienced.

Even still, we believe for the sake of the United States and its ideals, and for people who have suffered far too long, our American story of race must change. Those of us who commit to the reparations movement are taking a clear step to say we will do the work to make that happen, and we are inviting others to join us on this journey for justice, restitution, healing, and reconciliation.

This article was originally published by The Boston Globe.

David Gardinier founded the Fund for Reparations NOW!

Karen Hilfman is a founding member of White People for Black Lives and a board member of FFRN!

Editor’s note: David Gardinier and Karen Hilfman are available for interviews. Contact Don Rojas at naarc@ibw21.org