America’s Founding Fathers had some great ideas and some greatly disturbing ones.

Eight months after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream Speech” in Washington, D.C., another minister and activist arrived at the King Solomon Baptist Church in Detroit to give a very different kind of address. In his famous “Ballot or the Bullet” speech, Malcolm X dismissed King’s civil rights movement as weak and misguided, and he asked his fellow African-Americans to open their eyes.

“I don’t speak as a Democrat or a Republican, nor an American. I speak as a victim of America’s so-called democracy,” Malcolm X intoned. “You and I have never seen democracy — all we’ve seen is hypocrisy.”

For as long as the United States has been touting the virtues of freedom and democracy, it has struggled to implement them, and not just in our own tumultuous political times. OZY begins this exploration of the victims and hypocritical perpetrators of “America’s so-called democracy” with the troublesome views of the man who penned the words at the heart of the nation’s founding creed: “All men are created equal.”

***

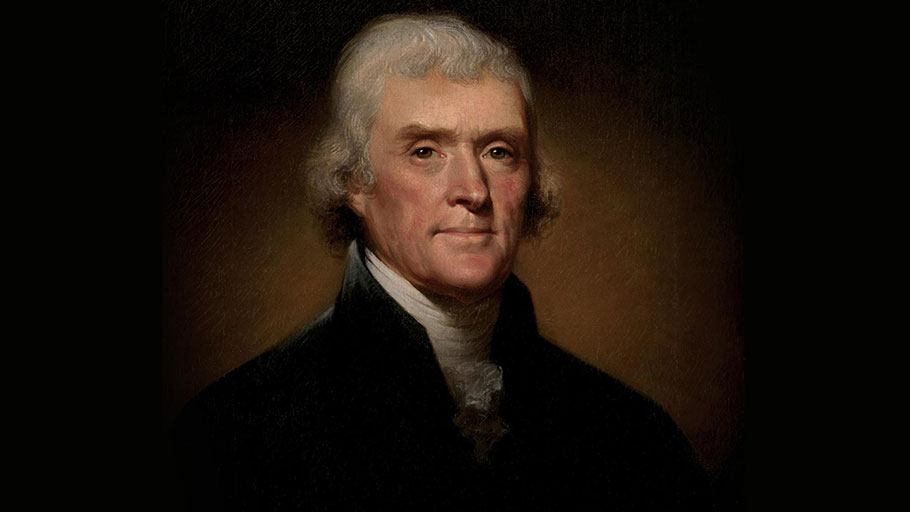

It’s a widely known fact that American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson owned slaves, and he is now regarded as having fathered six children with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. But less widely acknowledged or accepted is another disturbing fact that is hard to escape: Jefferson was almost certainly a white supremacist.

As historian Henry Wiencek chronicles in Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves, the third president’s view of slavery seems to have “evolved” through time, to use the parlance of today. For one thing, Jefferson’s father-in-law, John Wayles, was a slave trader, and six of his wife’s half-siblings were slaves, and the two frequently discussed the occupational and moral hazards of his profession. Before the Revolutionary War, Jefferson submitted an emancipation bill (under a different name) to the Virginia state legislature, and in a deleted part of the Declaration of Independence he even argued that “this execrable commerce” was a “cruel war against human nature itself.”

Jefferson felt compelled to address the shackled elephant in the room.

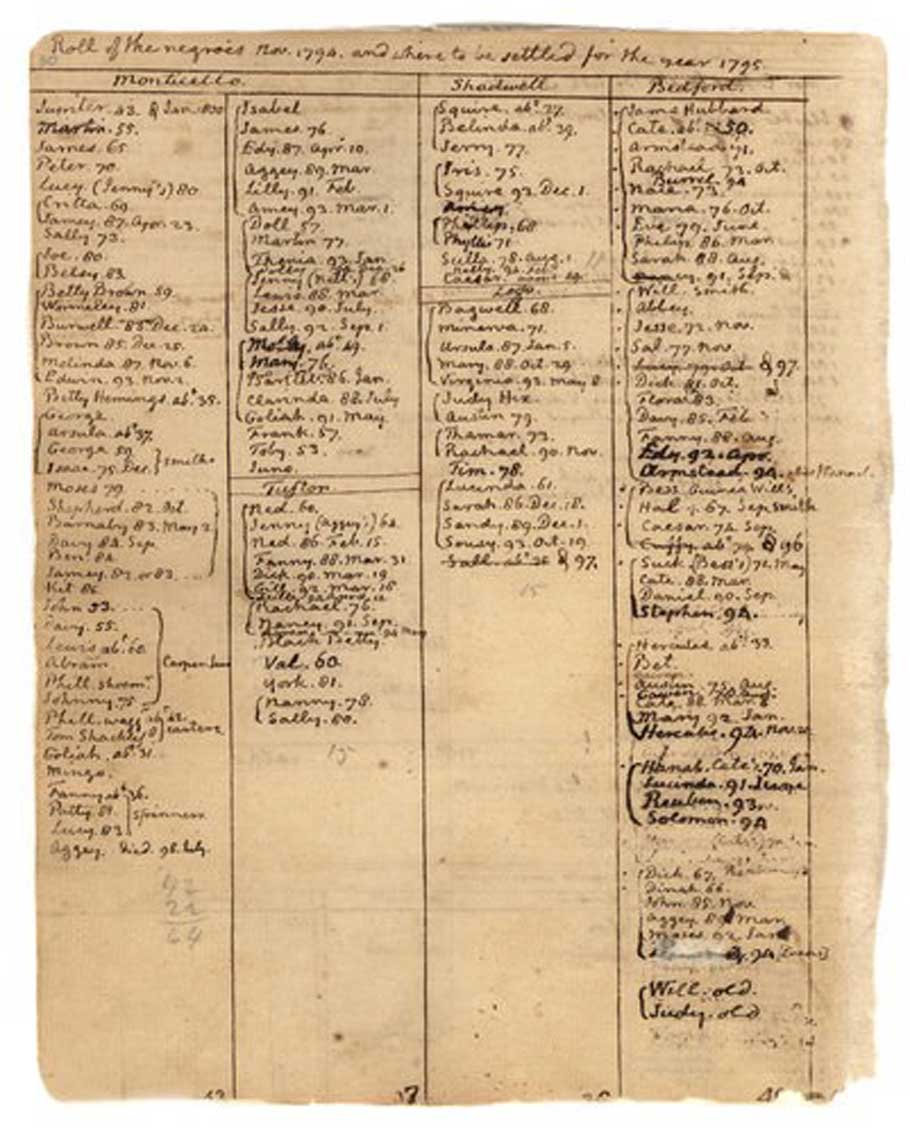

Then something seemed to change. During the 1780s and early ’90s, Jefferson’s abolitionist efforts ceased and for the next few decades he continued to be not only a buyer and seller of human beings, but an apologist for it. A number of theories for this shift exist, but Wiencek argues that it could be as simple as a growing recognition on Jefferson’s part of the commercial benefits of such an arrangement. “He realized the immense profits to be made from owning slaves,” says Wiencek. “He referred to the births of enslaved children as additions to his capital and urged neighbors to invest in slaves.” He also sold slaves to settle debts and took out the equivalent of a “slave equity” to rebuild Monticello. As Wiencek puts it, “Why would he part with such an extremely valuable asset?”

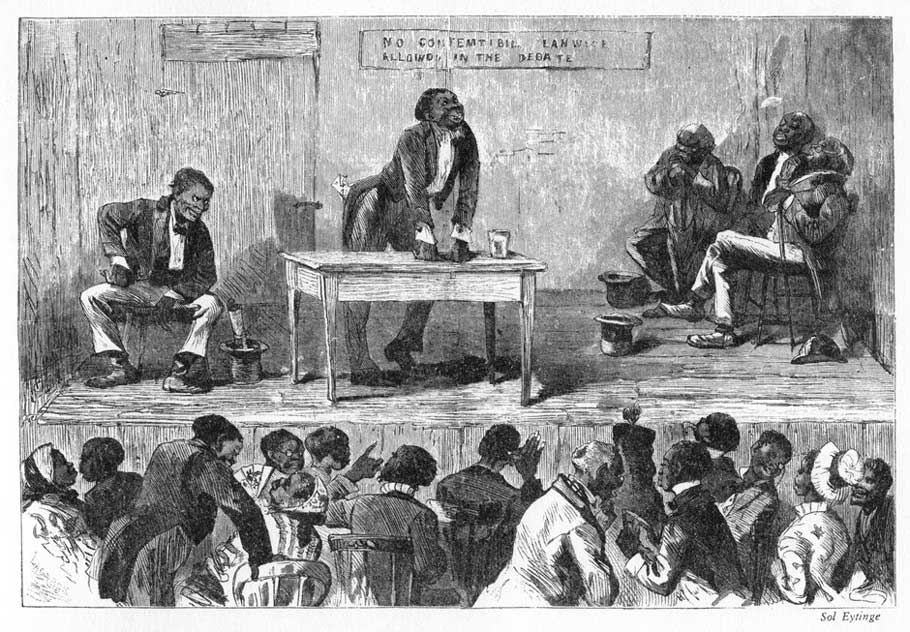

Blackville, an 1878 illustration. African-Americans are depicted in this racist caricature as illiterate and apelike. From Adventures of America, 1857–1900, by John A. Kouwenhoven. Source: The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images

In justifying his commercial holdings, Jefferson expressed some views about whites and Blacks having differences “fixed in nature” that would have made Jimmy the Greek cringe. One of the clearest statements of Jefferson’s perspective is found in his Notes on the State of Virginia, detailed answers he compiled in the early 1780s to a questionnaire from a visiting French diplomat, or, as Wiencek calls it, “the dismal swamp that every Jefferson biographer must sooner or later attempt to cross.”

The questionnaire did not address slavery but Jefferson felt compelled, in defending a young nation with an inferiority complex vis-a-vis France and Europe, to address the shackled elephant in the room and explain how such a practice persisted in a country allegedly founded on freedom, equality and natural rights. As Samuel Johnson once quipped regarding the Americans’ hypocrisy, “How is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?”

Jefferson does not portray slavery, or slaveholders, in a particularly positive light, observing how the practice harms both the manners and industry of whites: “No man will labour for himself who can make another labour for him.” But in the tract’s most infamous passages, he puts on his amateur anthropologist hat to make some startling observations. Citing skin color as the most obvious distinguishing feature, Jefferson argues that a slave’s darker skin pigment makes them less transparent, noting that an “immoveable veil of black … covers all the emotions.” As for the appearance of whites, he argues that their features, including hair, make them more sexually appealing, claiming that Black people are sexually attracted to white people “as uniformly as is the preference of the Oranootan (Orangutan) for the black women over those of his own species.”

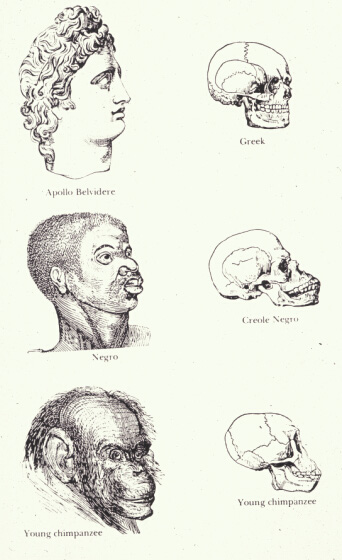

Illustration from Indigenous Races of the Earth (1857), whose authors, Josiah Clark Nott and George Robbins Gliddon, implied that “negroes” were inferior to white Europeans. Source: Public Domain/Wikipedia

You read that right. Not exactly as high-minded a sentiment as the Declaration’s stirring opening — and based on one dubious anecdotal account of apes raping African women — but Jefferson goes on to propound some further truths about Blacks that are neither true nor self-evident. The catalog of slaves’ biological inferiorities also includes observations like “a very strong and disagreeable odor,” “they require less sleep,” “their griefs are transient” and not only “in imagination they are dull, tasteless and anomalous” but also “in reason much inferior.”

Jefferson acknowledges that “further observation” is needed to verify his “conjecture” and that “to achieve certainty” slaves would have to be submitted to scientific analysis, including the “Anatomical knife.” But the conclusion he draws — one that justifies American slavery — is unmistakably clear: “It is not their condition then, but nature,” he concludes, “which has produced the distinction.”

The paradox of Jefferson the political philosopher and racist slave owner may fascinate us today, but should we even be applying our modern standards to judge his late-18th-century views? Yes, I think, and the standards of his era as well. Jefferson wrote Notes at a time when many other prominent Virginians were questioning slavery, and Quakers and other religious denominations were already opposed to it. “It is wildly wrong to say that condemnation of slavery is a modern, politically correct notion,” Wiencek says. “George Washington freed his slaves, as did many Virginians of Jefferson’s time, including his own relatives.”

A list of Jefferson’s slaves. Source: Public Domain/Wikipedia

Other Jefferson scholars disagree with Wiencek’s take on the progression of Jefferson’s views on slavery and Blacks, but there is no real disagreement about how disturbing the Founding Father’s beliefs on white racial superiority remain. As Paul Finkelman, the author of Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson, put it bluntly in The New York Times, those looking back at Jefferson must “confront the ugly truth: the third president was a creepy, brutal hypocrite.”

One of Jefferson’s own guiding maxims was Fiat justitia, ruat coelum — “Let justice be done though the heavens fall.” If we are to do justice to the life of one of American history’s leading figures, then we must also be willing to heed the dark clouds looming over that legacy.