How white Americans used lynchings to terrorize and control black people.

By Ed Pilkington in Montgomery, Alabama —

Vanessa Croft was driving home after work in Gadsden, Alabama, last month when she noticed something strange in her rear-view mirror. There were two huge flags bearing the starred cross of the Confederacy fluttering angrily behind her from the back of a menacing black pickup truck.

She had seen plenty of Confederate flags – almost every day she spots them on car licence plates or in windows in town. But this was different. It was after midnight, and as she drove the flags stayed behind her. She drove some more, they followed.

She turned into a McDonald’s, hoping that its surveillance cameras would protect her – they turned too, drawing up alongside her. Inside the truck were two white men who sat and stared at her. Croft, a 57-year-old black woman, stared back.

The truck kept trailing her all the way to her street, then disappeared as suddenly as it had come. But a chill lingered. “Two huge Confederate flags flapping in the night following me home. In Gadsden. In 2018. It still happens.”

The incident got her thinking about the secret that lay deep inside her family until just a few years ago. It concerned Uncle Fred, a beloved figure in her childhood who lived in New York. She knew him as her New York uncle, that’s all. Until her father told her the story.

Vanessa Croft stands in front of the EJI memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. Photograph: Brendan Gilliam

It was in the mid-1930s, and Fred was 15. He was out at work one day when a posse of white men turned up at the family home. Where was the boy, they demanded. A little white girl had been pushed off a porch and her father, incensed by such disrespect, had decided it was Fred who did it and had to pay, even though the girl swore it was someone else.

When the men were told that Fred wasn’t there, they left a message. Tell the boy we’ll be back for him tonight.

There was no doubt what they meant. Fred’s father knew, as all black townsfolk in Gadsden knew, what had happened to Bunk Richardson.

The 28-year-old had been seized a few years back by a local mob of white men in relation to the murder of a white woman in which he had played no part. They took him to a railroad bridge over the Coosa river on the edge of town and flung him over, leaving him hanging from a rope for several days for all to see.

Fearful that the same fate awaited him, Fred Croft fled. His father told him to leave town as darkness fell and never come back. And he never did.

At the age of 15 Uncle Fred fled north, never to return.

Vanessa Croft relates the stories of Fred Croft and Bunk Richardson – the teenager who escaped a lynching and the man who didn’t – at a spot that has profound resonance to her narrative. We are standing in the middle of a memorial square in Montgomery, Alabama, surrounded on all sides by brown metal cylinders of weathered corten steel.

On each of the cylinders, names have been engraved along with the counties in which they met their end. Some have just a few names, others 20.

The particular box under which we are standing, Etowah county, Alabama, in which Gadsden lies, has just one name: Bunk Richardson. Under it has been etched 02.11.1906, the date they placed the noose around his neck.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opens on Thursday, is a place unlike any other in the United States. Together with a new Legacy Museum which also opens this week, it addresses head on a subject that has been marked by a booming silence until now – the enforcement of white supremacy in America through racial terrorism in the form of lynching, as well as its other guises: slavery, segregation and modern mass incarceration.

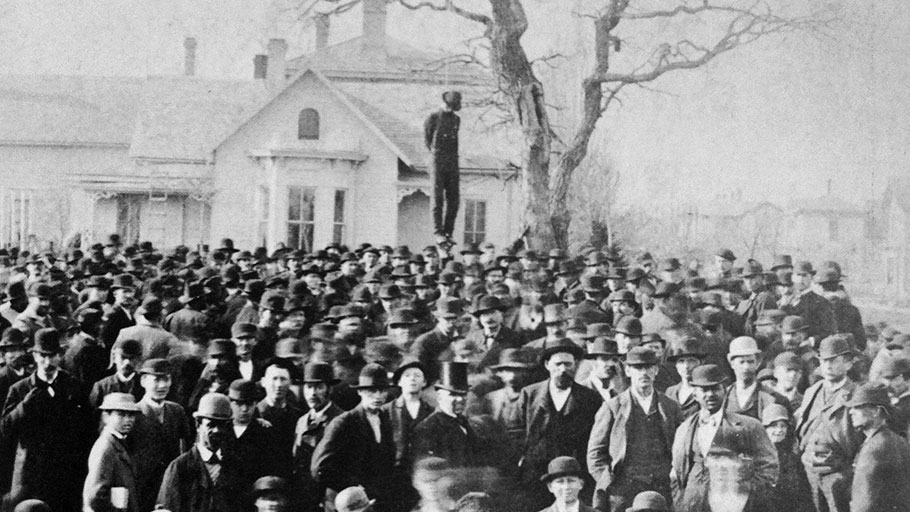

Lynching of Laura Nelson, May 1911, Okemah, Oklahoma, presented as a photo postcard. Stamp on reverse reads ‘unmailable’. Photograph: George Henry Farnum/1911

The memorial records and honors the more than 4,000 people of color, Bunk Richardson among them, who lost their lives to terror lynching. It is the brainchild of Bryan Stevenson, a civil rights lawyer who for the past 25 years has been a firebrand for justice in a region that is so often resistant to it. He has championed the most desperate and vulnerable in the deep south, from 125 death row inmates he has helped avoid execution to children as young as 13 condemned to die behind bars.

Having made his name through his not-for-profit group Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) fighting on the toughest frontline of the US criminal justice system, Stevenson has now turned his energies to exposing the historical causes of the country’s enduring racial wounds.

“I’ve been persuaded that the law will be insufficient to create justice if we don’t also create a consciousness about our history and address the burden that so many Americans carry,” he told the Guardian in Montgomery ahead of the opening.

Stevenson has never done anything by half measures, and his twin memorial and museum are no exceptions. The memorial sits audaciously atop a hill overlooking the heart of Montgomery. From its grounds you look down on the state capitol, the legislative beating heart of Alabama that acted as the first capital of the Confederacy and presides over a state constitution that to this day outlaws white and black kids going to school together: in 2004 and 2012 Alabamans held referendums on whether to remove the racist ban; both times the overwhelmingly white majority voted to keep it.

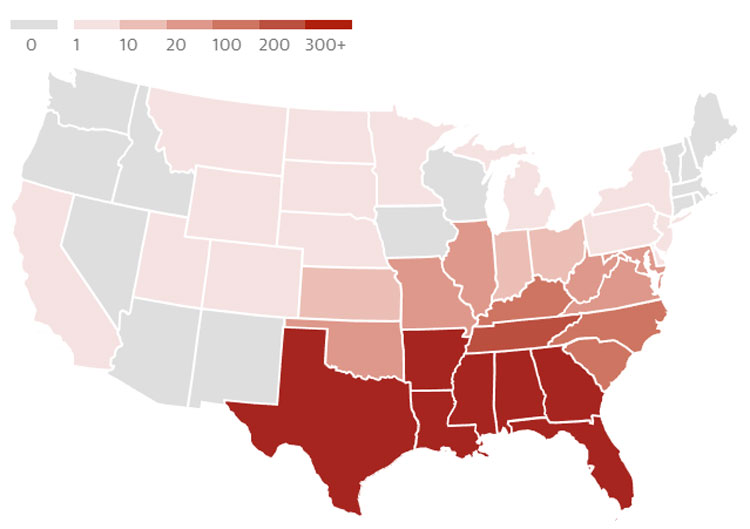

More than 4,000 lynchings occurred in the US between 1877 and 1950

Source: Equal Justice Initiative

You enter the memorial through a swath of lush grass, which lulls you into a false sense that the journey you are about to embark on will be soothing and serene. It is neither. As you walk through the four corridors that form the memorial square the sheer number of engraved names representing lynching victims begins to well up around you like swirling tides.

Inside the EJI memorial. Photograph: Human Pictures/Equal Justice Initiative

Then the floor begins to descend, giving the impression that the rusted steel monuments are rising up in front of you like so many bodies strung from a tree. They dangle above your head, swaying slightly in the wind, mimicking the bare feet of the lynched men that similarly swung above the heads of their white assailants standing beneath them grinning into the camera.

“We wanted to lift up this violence because that’s precisely what the perpetrators of lynching themselves wanted,” Stevenson said. “They wanted to lift it up because only by doing so did they have the power to terrorise, to taunt and torment entire communities of colour.”

Once the steel boxes have risen up high in the air, you turn a corner and come, with a jolt, face to face with the horrifying scale of lynching in America. Hundreds of monuments to the victims are hanging before you, neatly arranged in columns like the headstones of national heroes at Arlington cemetery, except these national heroes have never been recognised before today.

EJI has identified more than 4,384 lynchings by white people of people of colour in the main era when such racial terrorism stalked the land, 1877 to 1950. They spanned 800 counties, mainly in the deep south, each one of which is represented at the memorial with its own steel monument.

One of the myths of the lynching era was that black people were targeted for raping white women or for murder. But EJI’s research suggests that only a quarter of the lynchings involved sexual relations and less than a third related to allegations of violence.

Most frequently, the “crimes” committed were breathtakingly minor. Like shoving a girl off a porch, as Fred Croft found when he was forced to flee for his life. Jack Turner was lynched in Alabama in 1882 for organizing black voters. Bud Spears raised objections to the lynching of a black man in Mississippi in 1888, and for his pains was himself lynched. Many of the two dozen or so women who were lynched died because a mob couldn’t find their husbands or sons at home so grabbed them instead.

One of the most heartbreaking names in the memorial is that of General Lee. Not much is known about him, but it is likely that as a black man he took the name of Robert E Lee, commander of the Confederate States army that fought to keep his race enslaved, because he was under the delusion that it would somehow save his skin. It didn’t. Lee was lynched in 1904 in South Carolina for knocking on the door of a white woman.

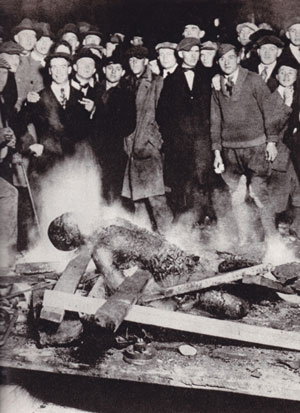

Huge crowds often turned out: 10,000 to watch Henry Smith, 17, tortured and burned on a 10ft-high stage in Paris, Texas, in 1893; 20,000 at the burning alive of Willy Brown in Omaha, Nebraska in 1919. Such was the communal complicity that sometimes entire white communities would attend – to a man, woman and child.

Sherrilyn Ifill, author of the definitive lynching history On the Courthouse Lawn, describes a common pattern: as soon as the public spectacle of the killing was over, white townsfolk would suddenly lose all memory of the event. No, they hadn’t seen anything, no they didn’t know who was responsible, and yes it was strangers from out of town who did it. “It was understood as an act of loyalty to be silent about the lynchings and who did them, and that act of loyalty was passed down, becoming a part of the community.”

As you walk around the memorial these stories roil around you. The space is quiet, but feels as though it should resound with ear-splitting, unearthly howling or wailing. Each name on every single metal monument stretching out before you represents a moment of unconscionable inhumanity and suffering.

It would be prurient to dwell on the details, yet nor should they be glossed over, as to do so would be to sustain the collective amnesia that has characterised America’s relationship with racial terrorism.

Here is the entry for Coweta county, Georgia, tucked away in one of the memorial’s corners. On it is stamped: “Sam Hose 04.23.1899”. Look behind those two words and three numbers and you discover that the lynching of Sam Hose was planned days in advance and witnessed by a crowd of about 2,000 white people.

Many had travelled on trains laid on for the occasion from Atlanta, some custom-provided for people coming straight from church. Platform criers hurried passengers along with the refrain: “Special train! All aboard for the burning!”

A crowd gathers after the lynching of two young African American men who were taken from the Grant county jail, in Marion, Indiana, and lynched in the public square. Photograph: Lawrence Beitler/Bettmann Archive

Hose was accused of murdering his white employer before assaulting the wife – claims that were all thoroughly debunked by an investigation launched by the great anti-lynching advocate and journalist Ida B Wells. In truth, the 23-year-old had acted in self-defence when his employer put a loaded gun to his head.

The classic image of the lynch crowd is of a mob of “white trash”, the unrestrained and uneducated dregs of society who knew no better. Incorrect.

As Wells’s research revealed, Hose’s death was actively instigated by many of white society’s most upstanding Christian leaders: the banker who urged his customers to “make an example of Sam”, the manager of one of the largest mills who called for a burning, the governor of Georgia who refused to stop it, the local newspaper that advertised it and egged on its readers.

They tied Hose to a sapling and laid kindling at his feet. As the flames began to lick, first they cut off his left ear, then his right. Next they cut the skin off his face, hacked off his fingers, slashed his legs, and opened up his stomach to pull out his entrails. They did so slowly, meticulously, so as to ensure that he remained conscious throughout.

Then they poured oil on the fire and watched him burn. The crowd, which included many women and children, looked as though it was having great fun. The only disappointment, as Wells’s investigation noted, was that the black man declined to give the participants the pleasure of hearing him beg for mercy. He never once cried out. His only utterance was a quiet groan: “Oh, Lord Jesus,” he said.

When it was all over, children and adults scrabbled among his remains for relics to be later cherished or sold, including his charred liver and bones.

For Bryan Stevenson, such barbarism, such sadism, served a purpose. It also exacted a heavy price.

“People were being asked to prove their commitment to white supremacy by their willingness to engage in ever more extreme forms of violence,” the lawyer said. “The problem with that is you get disconnected from decency and kindness, you get lost in it. Whether you were the person cutting off fingers or the person enjoying deviled eggs and lemonade as the spectacle unfolded, something tragic and destructive was happening to you.”

The body of Will Brown after being burned by a white crowd on 28-29 September 1919 in Omaha, Nebraska. Photograph: SeM/UIG via Getty Images

As he speaks, the exceptional nature of what Stevenson has created on top of the hill becomes clear. This is not another conventional addition to black historiography. Certainly, it explores and commemorates black experience. But it also powerfully dives into the warped psyche of white Americans prepared to participate in the gruesome mutilation of other human beings.

This is not academic history, it is red-hot political challenge. It challenges the state capitol down the hill, it challenges white-dominated towns and cities across the American south and beyond, and, yes, it challenges the current occupant of the White House. It is time, the new memorial says, to confront the sins of the past and recognise the tragic consequences of white supremacy.

It’s a provocative posture, and Stevenson knows it. “There are clearly going to be people who are provoked and disrupted and challenged by this, sure there will be. A lot of people will never come here, they are angered by the idea that this is something we have to talk about.”

Stevenson, standing on a mound at the center of the memorial, looked around the more than 4,000 names honoured here, and said: “People brought their children. They made their little kids watch human beings be burned or drowned or beaten. That has created a disease where we have become indifferent to the victimisation of black people. We have to treat that disease.”

The treatment continues down the hill in downtown Montgomery at the new Legacy Museum which traces the unbroken path of racial violence from slavery, through lynching and Jim Crow segregation to the modern era of drug wars and mass incarceration. The exhibition is fittingly located in a slave warehouse on Commerce Street (the commerce in question having been trade in slaves) just two blocks away from the auction house where black people were sold along with mules, carts and wagons.

Stevenson’s conviction is that slavery didn’t end in 1865, it evolved into lynching, then segregation and now into a modern dystopia where 2.3 million Americans are incarcerated and one in three black males born in America can expect at some point to go to prison.

He draws a single unbroken thread uniting all these manifestations of racial dominance: “The idea that black people are not the same as white people, they aren’t fully human or evolved, and are presumed dangerous and guilty. That’s why American society today is so non-responsive to shootings of unarmed black people, to disproportionate expulsion rates of black kids, to putting handcuffs on four- or five-year-old black girls – we’ve been acculturated to not valuing the victimisation of black people.”

Perhaps most controversially, he invokes a comparison with 9/11. On 11 September 2001 international terrorists killed 2,976 people. In response memorials were erected at Ground Zero, the Pentagon and Shanksville, Pennsylvania; Osama bin Laden and many of his henchmen were killed or imprisoned indefinitely in Guantanamo and around the world; the US military was mobilized for a war on terror that continues almost 17 years later.

In the lynching era, domestic terrorists killed at least 4,308 people. In response there have been no memorials until this day. Not a single perpetrator of a single lynching was ever convicted of murder.

“Many people of colour are left questioning,” Stevenson said. “Wait a minute, they say. I didn’t realise we had the capacity to fight a war on terror. Where were the soldiers, the planes, the tanks back when we were being terrorised?”

Stevenson hopes the memorial and museum will be the first step towards a process of truth and reconciliation on the model of South Africa and apartheid or Germany and the Holocaust. His ambition is that each of the 800 counties where lynchings occurred will set up their own copy of the rusted steel monument, which in turn will encourage an end to the silence and the beginning of discussion and healing.

There is undoubtedly healing needed in the Alabama town of Gadsden. Vanessa Croft said that the impact of her uncle’s flight had a lasting impact on her family. Six of her other uncles followed Fred’s example and exiled themselves from the state, joining the Great Migration in which 6 million black people fled north and west in part to avoid the lynching terror to cities such as New York, Detroit, Milwaukee or Los Angeles.

The Great Migration: states’ changing black population over six decades

Vanessa’s father was the only one of seven brothers who remained in Alabama.

Fred went on to have a good life in New York. He loved Harlem, worked in hotels, raised three boys of his own. He died in 1977, before Vanessa Croft had learned about his reason for leaving.

When Croft heard the story of what had happened to her uncle, and to Bunk Richardson before him, she was shaken up. “Gadsden is a beautiful place. But this was horrifying. How could people be so cruel?”

Details of Richardson’s death in particular haunted her. She kept turning over in her mind the knowledge that he had been so terrified when the mob dragged him to the bridge that his legs buckled beneath him.

“I started to think and look at the people of my town differently,” she said. “This mob, it was made up of the leaders of our town, the doctors, the lawyers, the teachers. To do something this terrible, you wonder where does that come from.”

And you wonder where did it go. “I think of the people I interact with on a daily basis, and I think to myself. Could you still do that today? Could you do that to me?”