Visitors at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, April 26. Photo by Bob Miller, Getty Images

While visiting the newly opened National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama — a hallowed and harrowing enshrinement bearing the names of over 4,000 black people lynched in the Jim Crow South — I was reminded of stories my grandparents told me as a child.

Stories of my great-grandfather, once chased by Ku Klux Klan members on horseback before swimming to safety, preferring possible death by drowning to murder by his countrymen. Stories of my great-grandmother, whose white partner was burned alive in his home for loving a black woman. Stories of uniquely American terrorism, seldom told and rarely reconciled.

But with this new memorial and its complementary Legacy Museum, the Equal Justice Initiative, which built them, may finally achieve reconciliation for such racial terror. By recognizing the lives lost to lynching and illustrating slavery’s evolution through the accounts of its victims — both past and present — the EJI teaches us how storytelling can be used to acknowledge America’s violent past and heal slavery’s long-standing wounds.

A Pilgrimage To The Past

As a descendent of American slaves, I felt my visit to the memorial in Alabama was less like a weekend away and more like pilgrimage — religious in that it was a time for reflection and a search for answers.

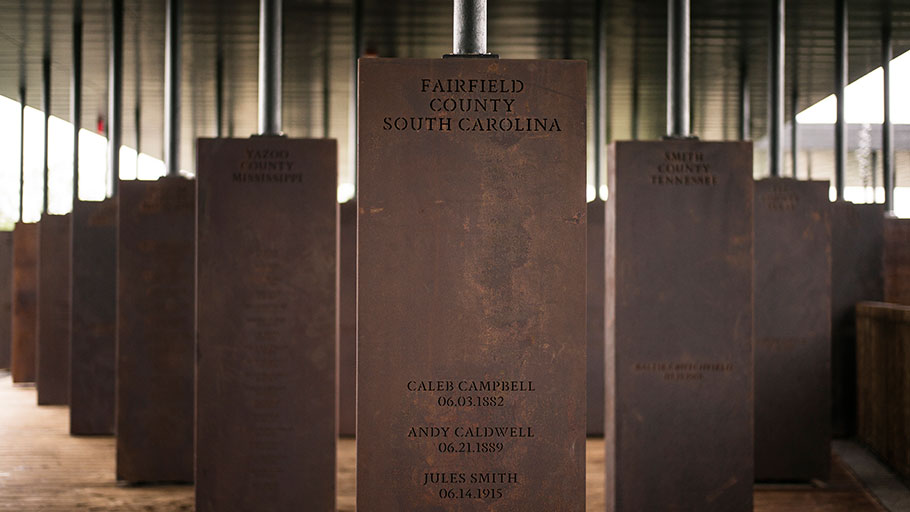

Upon entering the memorial, I was met with 800 coffin-shaped blocks — hanging as if from a noose and lifeless all the same. Oxidized by the Montgomery air, each was drenched in ever-changing hues of reddish-brown and etched with victims’ basic information: their names and the county and state where they were murdered.

At the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, markers display the names and locations of people killed by lynching. Photo by Bob Miller, Getty Images

For the majority of the victims listed, the memorial is their first instance of public recognition — the result of years spent by EJI lawyers delving into library archives, led by the group’s executive director, Bryan Stevenson. He has said in interviews since the memorial’s opening that his primary goal is to hold a mirror to America and help it progress by reflecting on its history of racial violence.

As I walked through the consecrated catalog of public lynchings — densely packed to emphasize its magnitude — the floor dipped until the blocks hung above my head, forcing me to feel the gravity of each honored life.

I wanted to savor the calm of the memorial, but standing amid a barrage of familiar names and counties, I was distressed by countless questions: Were any of the names listed members of my family? If so, how were they killed? What did they do to meet such a brutal and public death? What could I do to honor their lives?

I quickly sent a series of texts and calls to my extended family, including my 82-year-old grandmother — my last living grandparent, a woman of unmatched grace and strength. I asked her if she knew of anyone in our family who was a victim of racial violence, and she shared a story of family member who, after learning that white townspeople were planning to lynch him, disguised himself and fled, never to be seen again. When I asked why he was targeted, her response was jolting. She said, “Around town, rumors were spreading that he had spoken to a white woman.”

Many of the memorial’s lynching descriptions — plainly described on a gallery of narrow black placards beneath the elevated blocks — reflected the same triviality. Like the family member in my grandmothers’ story, the victims listed were lynched as result of painfully immaterial actions:

“John Stoner was lynched in Doss Louisiana, in 1909 for suing the white man who killed his cow.”

“Robert Morton was lynched in Rockfield, Kentucky, in 1897 for writing a note to a white women.”

“A black man was lynched in Millersburg, Ohio, in 1892 for ‘standing around’ in a white neighborhood.”

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo by Bob Miller, Getty Images

The stories shared on other placards spared few graphic details, describing lynch mobs by the thousands who burned black men, women and children alive. Mere decades ago, lynchings commonly occurred in town squares and served as public warnings to black residents — reminders that even standing around while black could result in death.

Reading the descriptions, I couldn’t help thinking of how, over a century later, bias still results in black people being killed without reason.

When Stephon Clark was fatally shot by two Sacramento, California, police officers in March, the officers initially claimed he was holding weapon. Shortly after his death, it was revealed that he was unarmed. Not unlike the Skittles held by Trayvon Martin and the toy held by Tamir Rice, a cellphone was the only item Clark held.

Whereas black people were presumed to be dangerous in the Jim Crow South for standing around — and killed as a result — they are now killed for fitting a description, being in a problem area or holding seemingly any object. Whereas thousands once gathered to watch black people be lynched, millions can now tune in to video recordings and livestreams to watch police brutality unfold.

Lynching hasn’t disappeared; it has evolved.

The Progression Of Slavery

While its memorial is already inspiring institutions to reconcile their troubled pasts, the EJI is primarily concerned with how the legacy of slavery is plaguing modern governmental institutions — namely the criminal justice system and death row. As of 2016, Stevenson and the EJI helped save 125 wrongly condemned prisoners from the death penalty, including Anthony Ray Hinton. Before Stevenson’s support helped get Hinton’s case dismissed, he spent 30 years awaiting execution for a crime he didn’t commit.

The ghost of slavery is the focus of the EJI’s Legacy Museum, which opened with the memorial last week.

A sculpture of enslaved people at the entrance to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Photo by Bob Miller, Getty Images

In every corner of the museum, stories of racial violence detail slavery’s horrors. Holograms enact true slave accounts. Slave auction propaganda fills walls, bleeding through their margins. Mock prison phone booths re-create conversations with people on death row. Cries for help ring through letters from incarcerated individuals seeking protection from officers’ abuse.

By grounding each story in past and present policies, the museum details how the criminal justice system has always been used as a tool for suppression.

One of slavery’s iterations was convict leasing, in which black people who committed criminal acts were leased to other citizens and forced to work for no pay. This thinly veiled form of slavery generated 73 percent of Alabama’s revenue by 1898, according to the museum.

Fast-forward to the 1970s and President Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, which targeted and criminalized black people, catapulted the prison population from 300,000 to over 2 million in just 40 years. Today black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons, on average, at five times the rate of white Americans.

Such a clear chain of events leads to one conclusion: Slavery never ended, it evolved.

Even after they were “freed,” my American ancestors — the roots of my family tree — feared for their lives every day. But their prayers persisted. Prayers that their countrymen would see the hollowness of their hatred. Prayers for a moral shift in a nation that never cared to keep them safe. Prayers that their stories — filled with horror but defined by hope — will always be told.