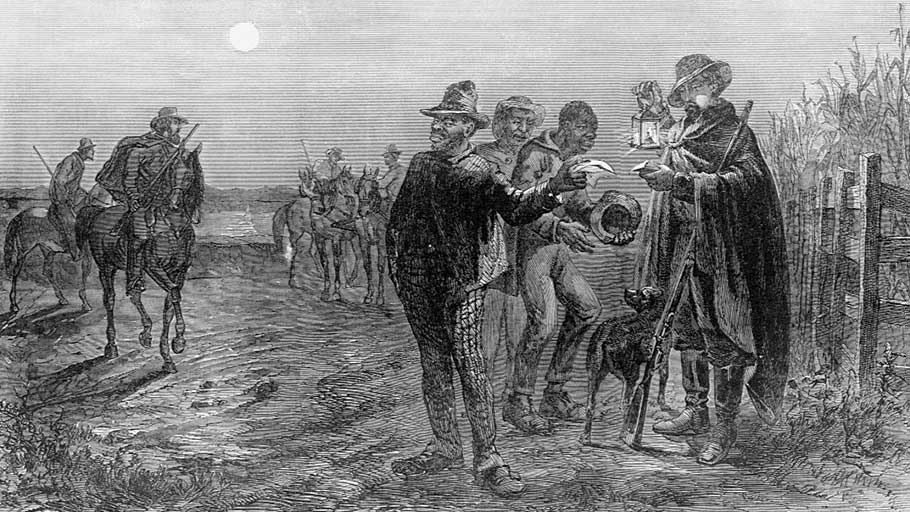

Slave Patrol – Photo by Corbis via Getty Images

From the beginning, some Americans have been able to move more freely than others.

They were called patrollers or, variously, “paterollers,” “paddyrollers,” or “patterolls,” and they were meant to be part of the solution to Colonial America’s biggest problem, labor. Unlike Great Britain, which had a large, basically immobile peasant class that could be forced to work for subsistence wages, there weren’t enough cheap bodies in America to do the grunt work. If you were a planter looking to make your fortune in rice or tobacco—the New World’s cash crops—you had to size up to industrial scale, and for that you needed bodies, armies of bodies, a labor force that could be made to work for terms no less brutal than those inflicted on the miserables of Europe.

Native Americans weren’t the solution, not after disease, war, and murderous forms of forced labor reduced their number by half. Indentured servants were imported, but in numbers too few to fill the void, and they had a habit of running off: the wide frontier beckoned, all that empty space for sass-mouths and malcontents to vanish into. So it became Africans. Jamestown received its first cargo of enslaved humans in 1619, a dozen years after the colony’s founding: “20 and odd Negroes,” according to records, the first installment on the estimated 455,000 who would eventually land in North America.

Control of this new labor force would be key; mutiny was the great fear. By the early 1700s, a comprehensive system of racially directed law enforcement was well on its way to being fully developed.

Certain people, granted power, can be counted on to abuse those under their authority just because they can

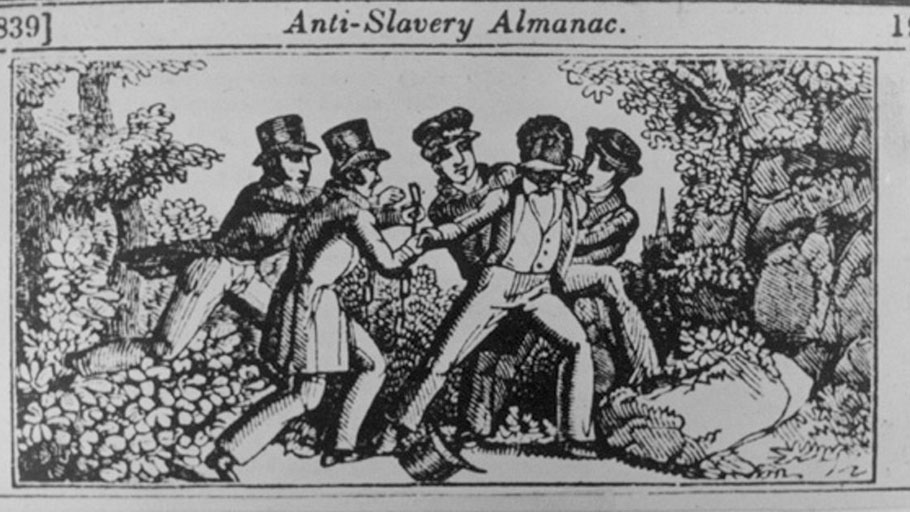

This was, in fact, the first systematic form of policing in the land that would become the United States. The northeast colonies relied on the informal “night-watch” system of volunteer policing and on private security to protect commercial property. In the southern colonies, policing’s origins were rooted in the slave economy and the radically racialized social order that invented “whiteness” as the ultimate boundary. “Whites,” no matter how poor or low, could not be held in slavery. “Blacks” could be enslaved by anyone—whites, free blacks, and people of mixed race. The distinction—and the economic order that created it—was maintained by a legally sanctioned system of surveillance, intimidation, and brute force whose purpose was the control of blacks. Slave patrols, or paddyrollers, were the chief enforcers of this system; groups of armed, mounted whites who rode at night among the plantations and settlements of their assigned “beats”—the word originated with the patrols—seeking out runaway slaves, unsanctioned gatherings, weapons, contraband, and generally any sign of potential revolt. They were the stuff of lore and songs:

Run Nigger run, Patty Roller will catch you, Run Nigger run

I’ll shoot you with my flintlock gun.

Run nigger run, Patty Roller will catch you, Run, nigger run, you’d better get away.

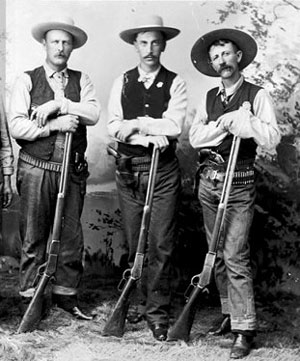

Slave patrols usually consisted of three to six white men on horseback equipped with guns, rope, and whips. “A mounted man presents an awesome figure, and the power and majesty of a group of men on horseback, at night, could terrify slaves into submission,” writes Sally Hadden in her fine and useful book Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Among other duties, paddyrollers enforced the pass system, which required all slaves absent from their master’s property to have a pass, or “ticket,” signed by the master indicating permission for travel. Any slave encountered without a pass was subject to detention and beating on the spot, although possession of a valid pass was by no means a guarantee against beating.

Three Slave Patrollers or “Paddyrollers”.

Certain people, granted power, can be counted on to abuse those under their authority just because they can; one imagines moreover that gratuitous beatings relieved the tedium and fatigue of nightlong patrols and served to reinforce the notion of who was boss. The paddyrollers’ authority extended to patrolling plantation grounds and entering slave quarters, where the presence of books, writing paper, weapons, liquor, luxury items, or more than the usual store of provisions was cause for beating. “Gatherings”—weddings, funerals, church services—were grounds for beating, writes Hadden. Mingling with whites, especially poor whites, or any “loose, disorderly or suspected person”: beating. Back talk: beating. Dressing tidily: beating. Singing certain hymns: beating. Even best behavior could earn a lick: “Elige Davison, another former Virginia slave, remembered that as bondsmen lay asleep in their own quarters, patrollers would enter and lightly hit them with a whip to see if they were truly tired and asleep at the end of the workday,” Hadden writes. For an enslaved woman, a beating might well be the least of her worries.

The system continued largely intact after Emancipation and the defeat of the Confederacy. Legally sanctioned slave patrols were replaced by night-riding vigilantes like the Ku Klux Klan, whose white robes, flaming torches, and queer pseudo-ghost talk were intended for maximum terrorizing effect. Lynching and shooting took place alongside the more traditional punishments of beating and whipping; blacks’ economic value as slaves had evaporated, and with it the constraints on lethal force that had offered some measure of protection under the old system. White supremacy continued as the dominant reality for the next hundred years, a social and psychological reality maintained by terror, surveillance, and the letter of the law. Its power was such that even the New Deal—the most profound reordering of American society since the Civil War—left white supremacy intact. Twenty-six lynchings were recorded in Southern states in 1933. An antilynching bill was defeated in Congress in 1935. Southern blacks’ awareness of antebellum history was acute, naturally enough given that they were living it. “Even seventy years after freedom came,” Hadden writes, “one former bondsman declared he still had his badge and pass to show the patrol, so that no one could molest him.”

We don’t have to know the particulars of history in order to live it in our bones. Sometimes history arrives as a sense of the uncanny, the peculiar weight of certain words and acts, a suffusion of dreadful power. We might suppose the pass system is long gone, but there it is in stop-and-frisk, in racial profiling, in the reflexive fear and violence of our own time. Trayvon Martin, 17 years old, walking down the street just minding his own, killed by a self-anointed, night-riding, so-called neighborhood watchman. Sandra Bland, died in a Texas jail after being pulled over for failure to signal a lane change. Walter Scott, stopped by police in North Charleston for an allegedly broken taillight, shot to death with eight bullets in his back. Philando Castile, popular school cafeteria supervisor, shot dead in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, during a traffic stop for, allegedly, a broken taillight (accounts differ); records reveal that he’d been pulled over no fewer than 52times by local police in the preceding 14 years and owed over $6,000 in outstanding fines. That $6,000 in fines opens the window onto another ugly echo of times past, the use of law enforcement to extract profit from black and brown people.

Michael Brown’s death at the hands of Ferguson police led to the exposure of a municipal regime that deployed police less for the sake of public safety than as a means of plundering the African-American community. In 2010, Ferguson’s finance director informed the police chief that “unless ticket writing ramps up significantly before the end of the year, it will be hard to significantly raise collections next year.” A new “I-270 traffic enforcement initiative… to fill the revenue pipeline” is plainly documented, and by Oct. 31, 2014, the municipal courts of Ferguson, a town of 21,000 residents (two-thirds of whom are black), had handled no fewer than 53,000 traffic cases that year. By 2015, more than one-fifth of the town’s revenue would come from fines and fees. The community’s frustration after years of harassment, abuse, and humiliation at the hands of the police would finally explode in the protests that followed Michael Brown’s death.

Some facts sit heavier in the gut than others. It may be that the American brain is wired for certain cues, or maybe it’s just the nature of systems of control, systems that grant or withhold sanction to move about, to work, to vote, to be secure in your home and body, to be free of suspicion absent evidence to the contrary. Sanction, in other words, to exercise your full humanity. Slave patrols and passes, the Klan, Jim Crow—these are historical incarnations of a social order that held people of color to less-than status, the necessary corollary to white supremacy.

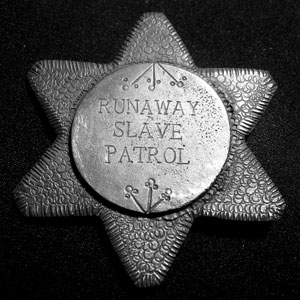

Slave Patrol

One doubts that Donald Trump knew the first thing about the pass system and paddyrollers when he took up the birther movement in 2011, employing lies and the cheapest sorts of innuendo to mainstream the allegation—the outright fantasy—that Barack Obama was not a genuine U.S. citizen. Trump, that master plumber of the American psyche, intuited the heat in the allegation, its potential for exciting the country’s ingrained racism. You couldn’t very well send night riders in full conehead regalia to burn a cross on the White House lawn in hopes of running the Obamas out of town, but you could harass and attack by other means, wage a 21st-century version of vigilante warfare on behalf of white supremacy.

By attacking Obama’s claim to citizenship, Trump tapped into the toxic confluence of racism and economics that’s organized life in America from the very beginning.

And so it went: the black man didn’t belong in the White House because he wasn’t a real American. He was an interloper, a pretender. Less than American. Which, of course, has been exactly the issue for people of color in America for 400 years, the issue brought into high relief—the schizophrenia inscribed by the country’s own hand, in effect—by the fine ideals expressed in the founding documents. All men created equal. Certain inalienable rights. So who is a “man”? Who is to be counted among “we the people”? Who is entitled to full enjoyment of the God-given rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and the protection and exercise of those rights as provided by the laws of the country? Trayvon Martin clearly wasn’t. Zimmerman walked, and it became necessary to say what in a just society would go without saying: Black lives matter.

The great divide in America has always been the color of skin, the presumptive and usually final criterion. Whiteness is law, legitimacy, citizenship, the benefit of the doubt. Not-white is doubt. Not-white has to prove, not just once but over and over: 52traffic stops. Can a white person even imagine? For 52 times Philando Castile had to stop and show his papers, keep his cool, say yes sir, no sir. Had to check the fury that surely rose in him with every stop, every new harassment and humiliation. This remarkable record of self-control should properly be called superhuman. A certain kind of gasbag politician loves to yatter at minorities for their alleged dearths of “personal responsibility,” yet these pols remain blind to a form of strenuous personal responsibility that’s enacted in some fashion several million times a day by people of color in America.

By attacking Obama’s claim to citizenship—by insisting that he produce a particular piece of paper in form and substance satisfactory to the race police, in their sole discretion—Trump tapped into the core of the American anthropology, the peculiarly toxic confluence of racism and economics that’s organized life in America from the very beginning. That the birther claim lacked even the slightest basis in fact was surely part of its power, that it existed so blatantly in the realm of racial animus. No night riders, no burning crosses, but there are other marginally less florid means of making the point. Dog whistles and codes. Racism hiding in plain sight. Birtherism was a dog whistle blown through a megaphone, and Trump rode it to the top of the polls in 2011, only to decline going head-to-head with Obama when he had the chance. He was still riding the birther wave as 2016 approached, but with the official launch of his candidacy in June 2015, Trump did something no mainstream candidate for president had done in a generation. He threw away the dog whistle.

They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.

An agenda he elaborated over the next 18 months with the wall, the illegal-immigrant-atrocity stories, the proposal to ban all Muslim immigrants, his smirking approval when his supporters beat Black Lives Matter protesters, the assertion that President Obama was “the founder” of ISIS, and in the wake of the Orlando massacre, that Obama either “doesn’t get it or he gets it better than anybody understands.”

For those of us of a certain age, it was a time warp, a fever-dream blast from the past. Who would have thought that George Wallace would be reincarnated in American politics as a New York City real estate tycoon? Wallace, that Brylcreemed banty rooster of a man, fighting cock of the racist Southern walk, and four-term governor of Alabama who thundered in his first inaugural address, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” He flamed across the national stage for 20 years, a dart-eyed, snarling prophet of the honky apocalypse.

He ran for president four times. As the American Independent Party’s nominee in 1968, he won five Deep South states and 46 Electoral College votes. That same year, Norman Mailer mused on the volcanic potential that Wallace touched but couldn’t fully tap, the power imminent in white America’s obsession with “the Negro problem” and its simmering, psychopathically suppressed guilt over the demonstrably valid claim that, as Mailer put it, “America’s wealth, whiteness, and hygiene had been refined out of the most powerful molecules stolen from the sweat of the black man.”

Wallace ran too hot for the ’60s and ’70s. Times had changed, and the racial concerns of variously aggrieved, enraged, neurotic whites had to be addressed by cooler means. But in 2016, Trump brought back the heat—and won. It seems that history has led us in a circle back to Alabama days, a circle so wide, so encompassing of far horizons, that we hadn’t known this journey that looked so much like progress was in fact a fantasy, a happy story we told ourselves along the way.

***

“Our country has changed,” wrote John Roberts, chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, in 2013. The case was Shelby County, Alabama v. Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General, and the chief justice, author of the majority opinion, was insistent on this point. “‘[T]hings have changed in the South.’” “[H]istory did not end in 1965.” “Nearly 50 years later, things have changed dramatically.” “[O]ur Nation has made great strides.” At issue in Shelby County was the constitutionality of sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (as reauthorized by Congress for the fourth time in 2006), which required states and certain counties with histories of racial discrimination to obtain “preclearance” from the Department of Justice before implementing changes to their election laws. Preclearance had been crucial in curbing racial discrimination in voting, Roberts conceded, but the remedy was no longer relevant to current conditions. Congress had reauthorized the Voting Rights Act in 2006 based on facts “having no logical relation to the present day,” wrote the chief justice. “‘Blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare.’”

Runaway Slave Patrol Badge

Smart white men acting stupid will be the death of America. John Glover Roberts Jr. is a white man, by all accounts a very smart one: summa from Harvard College, magna Harvard Law, Supreme Court clerk, impressively useful to his bosses in the Reagan-era Department of Justice, highly successful in private practice. His demeanor, obliged by pleasant, wholesome features and untroubled blue eyes, projects warmth, decency, and thoughtfulness, traits amply confirmed by peers and subordinates alike. In order to rule as he did in Shelby County—that Congress acted irrationally in reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act, which renders the preclearance remedy unconstitutional—Chief Justice Roberts had to place his own judgment over that of Congress (where the vote was 390–33 in the House, and 98–0 in the Senate, for reauthorization), President George W. Bush (who signed the bill into law within a week of its passage), and a legislative record that exceeded 15,000 pages, a record packed with reports, case studies, and the sworn testimony of scores of witnesses in support of the bill.

Smart white men acting stupid will be the death of America.

Chief Justice Roberts disagreed, in effect preferencing his own version of reality for that portrayed in those 15,000 pages of testimony, as vetted and endorsed by both houses of Congress and further endorsed by the president. The hubris of it takes your breath away. Here is a white man who has spent his youth and adult life in the highest reaches of the American establishment, a world where the security of one’s body is rarely at issue, a world of offices, computers, climate control, of orderly meetings and civil discourse, starched shirts, polished shoes—“hygiene,” to echo Norman Mailer—a world where people take their showers before work, not after. You don’t go hungry in that world; you don’t worry where your next meal is coming from, or the rent money, or whether you can go to the doctor when you’re sick. You work hard, no question, and it’s the best kind of work, interesting, stimulating, remunerative. It’s an entirely reasonable life to lead, nothing mean or dishonorable about it, and yet in the final analysis, it’s a relatively narrow slice of experience. It can encourage a kind of innocence—fantasy might be the better word—about the fact of one’s whiteness. Its neutrality. Its basic disinterest. What could be fairer, more equitable, more quintessentially American than color-blindness? A level playing field for all, no preferences or special treatment. Measures such as affirmative action and racial quotas—however necessary, and necessarily temporary, they may be—are viewed as aberrations, departures from the universal neutral of the good American norm, justified only by the most extraordinary circumstances.

But affirmative action and racial quotas have always been the American norm. To borrow a phrase from H. Rap Brown, racial preference is as American as cherry pie. For proof, we have the long history of racial preference that for hundreds of years produced all-white juries, city councils, legislatures, police forces, electorates, student bodies, faculties, executive suites, and labor pools.

The country has changed, Chief Justice Roberts insisted in Shelby County. “If Congress had started from scratch in 2006, it plainly could not have enacted the present coverage formula.” As if the “scratch” that Congress would have started from in 2006 would not, in the absence of the Voting Rights Act, have looked a lot like the America of 1965. But to a well-nourished, physically and financially secure white man comfortably settled in the lap of the establishment, it doubtless does look pretty good on the race-relations front. Though not perfect, no. “[V]oting discrimination still exists; no one doubts that.” Still and all, how far we’ve come as a country, yes indeed. Somewhat. Sort of. Some of the time. The record before the court provided a vast and detailed chronicle of the extent to which the country hasn’t changed, and the relentless pressure to undo the changes won. Yet in the chief justice’s judgment—in his experience, for what is judgment but the sum of experience brought to bear in the moment—Congress had acted irrationally, those 15,000 pages of evidence aside, in reauthorizing preclearance.

You could call this the “soft” psychology of white supremacy, as opposed to the more febrile mentality of neo-Nazis, Klanners, the alt-right crowd. White supremacy by default—a failure to see beyond whiteness as the presumptive norm, as the neutral and natural order of things. This is, ultimately, a failure of empathy, which is to say a failure of moral imagination, but Chief Justice Roberts didn’t even have to exert so very much of his imagination to clue into the state of things. Evidence of racist revanchism was as close as his right elbow every time he gaveled the court into session, for there sat Antonin Scalia, who as the senior associate justice occupied the seat of honor at the chief’s right. Amid his long career of professional skepticism toward civil rights and affirmative action, Scalia was capable of such openly racist screamers as this, offered during oral argument in an affirmative action case, when he said minority students would benefit by attending “a less advanced school, a slower-track school where they can do well.” And this, during oral argument for Shelby County itself, when Scalia observed of the 2006 reauthorization:

“And this last enactment, not a single vote in the Senate against it. And the House is pretty much the same. Now, I don’t think that’s attributable to the fact that it is so much clearer now that we need this. I think it is attributable, very likely attributable, to a phenomenon that is called perpetuation of racial entitlement. It’s been written about. Whenever a society adopts racial entitlements, it is very difficult to get out of them through normal political processes. I don’t think there is anything to be gained by any senator to vote against continuation of this act. And I am fairly confident that it will be re-enacted in perpetuity unless—unless a court can say it does not comport with the Constitution.”

“A phenomenon that is called perpetuation of racial entitlement.” And “it’s been written about.” Justice Scalia spoke the truth, though not in the way he intended, which is to say he didn’t know what he was talking about. There is, in fact, a phenomenon of perpetuation of racial entitlementin America, and it’s been written aboutby, among others, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Albert Murray, Frederick Douglass, Michelle Alexander, Zora Neale Hurston, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Mark Twain, Jean Toomer, Alice Walker, Claudia Rankine, Ralph Ellison, Tiphanie Yanique, August Wilson, Jesmyn Ward, Angela Flournoy, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Colson Whitehead, Morgan Parker, and many more.

“Very difficult to get out of them through normal political processes.” Justice Scalia was channeling the wisdom of the ages that day. We are for a fact still mired in the racial entitlementsthat came in with that slave ship in 1619, a social order that has so far produced the deadliest war in America’s history and many thousands of casualties before and after, the victims of conflicts that might be safely described as not through normal political processes.

The phenomenon known as “political correctness” is the struggle to supplant the default American identity of mythic whiteness with a truer, more complex identity

Scalia and Roberts were adhering to a fantasy, a perfect inversion of the reality that those writers on the phenomenon of the perpetuation of racial entitlement have always insisted on. The reality—the indisputable record, if you will—of black duress, black suffering, the theft of black labor, the fullness of black humanity, all the strands of the counternarrative to the heroic American fantasy that places whiteness in the starring roles, that makes whiteness the very definition of “American.” Trump bullied his way to the presidency on the power of that fantasy, all the potent, half-mad paranoias bound up in birtherism, the wall, the blaming and berating of Mexicans, Muslims, immigrants, Obama, Black Lives Matter, all the people and powers who’d supposedly betrayed the “real” America. The “real” America, white America, was strong and good and guiltless. “Real” America had nothing to apologize for.

“The grand aim of the [Voting Rights] Act,” Justice Ginsburg wrote in her Shelby County dissent, “is to secure to all in our polity equal citizenship stature.” Equal citizenship stature. Not less-than; not contingent; not the old American anthropology of dehumanizing, of decitizenizing, people of color, but full recognition of one’s humanity under the law, with equal right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Black Lives Matter gets at the same point. When Trayvon Martin’s killer walked, “black lives matter” located America’s failure with surgical precision. There would be no recourse for this young man’s unjustified death, no punishment, no assignment of guilt, no recognition by the system of this ultimate wrong. A starker demonstration of the less-than status of Trayvon Martin’s right to life cannot be imagined.

Trump reserved his special contempt for “political correctness,” which seemed to represent for him not just an agenda for supplanting the “real” America, but a very real and present threat to his ego. When it comes to the national psyche, Trump has great instincts—give him that. He was entirely right to identify political correctness as his enemy, insofar as it aspires—as it does—to a reinvention of American identity. And therein lies the revolution, “the deep and mighty transformation” that James Baldwin saw as America’s only hope. “Political correctness” denotes far more than linguistic temporizing and hypersensitive undergrads, but if the term has lately been rendered too small to carry its genuine revolutionary weight, we could try for a substitute. “Historical correctness,” say. Or “reality connect.” “Eyes.” “Knowledge.” “Getting a fucking clue.” Because at its heart, the phenomenon known as “political correctness” is the struggle to supplant the default American identity of mythic whiteness with a truer, more complex, more various identity—one that contains all of America’s historical reality as it plays out in the life of the country with each new day.

Runaway Slave Patrol Badge

“We are our history,” James Baldwin wrote of the American nation. “If we pretend otherwise, to put it very brutally, we literally are criminals.”

I attest to this:

the world is not white;

it never was white,

cannot be white.

white is a metaphor for power,

and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.

Which is another way of describing our history: profit proportionate to freedom, plunder correlative to subjugation. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank. James Baldwin is handing us a bomb with those words, all the truth of America compressed in that sentence like a teaspoonful of dead-star matter that weighs more than a thousand Earths. American society, the American anthropology, has from the start been organized on the invention of white supremacy. Allegiance to a certain kind of economics required it, and to ignore or deny the implications of these basic facts is to choose to live in a fantasy. “Make America Great Again” was yet another stroke of Trump’s salesperson genius. “Great” for whom, exactly? “Again,” with reference to which particular era? Trump gave us the answers plainly enough over the course of his campaign, he was no less clear in his agenda than a George Wallace or a David Duke, and his election should be viewed—must be viewed—as a triumph of that brutal anthropology.

Baldwin, again:

“What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a “nigger” in the first place, because I’m not a nigger, I’m a man. But if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need him. The question that you’ve got to ask yourself, the white population of this country has got to ask itself… If I’m not the nigger here and you invented him, you the white people invented him, then you’ve got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that, whether or not it is able to ask that question.”

Trump’s election represents a great turning away from that question. Trump sold us, or a good many of us, on the fantasy, but for a consummate salesperson such as he, it wasn’t all that hard a sell. Fantasy offers certainty, affirmation, instant gratification, a way to evade—for a while, at least—the reality right in front of our face. It’s so much easier that way, but perhaps we’re fast approaching the point where the fantasy can no longer be sustained. The evidence won’t shut up; it insists and persists, and in this, all those writers on the phenomenon of the perpetuation of racial entitlement, the James Baldwins and Toni Morrisons, have succeeded. And for the hard-core fantasists, we have video: the last moments of Walter Scott, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice are now part of the record. Consciousness—historical consciousness, political consciousness—has been raised to critical mass, and to suppress it, to try to stuff it back in the box along with all its necessary disruptions and agitations, will destroy the best part of America. The promise of it, the ongoing project. The possibility.

***

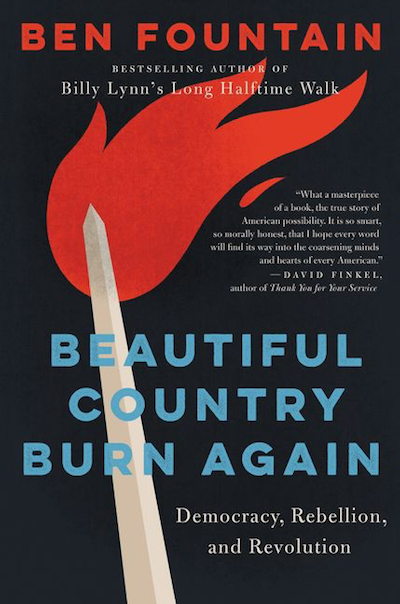

From the book Beautiful Country Burn Again by Ben Fountain. Copyright © 2018 by Ben Fountain.

To be published by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.