Author’s note: “Represent NYC” is a weekly program produced by Manhattan Neighborhood Network (MNN). The show’s guests usually discuss topics like affordable housing, education policy and domestic violence. I was invited to discuss the New York Times’ 1619 Project and the long-term impact of slavery on New York and American society for a Black History Month broadcast. This post includes the questions I prepared to answer and notes for my responses. New York will soon need its own 1626 Project. 1626 was the year that the Dutch West India Company brought the first eleven enslaved Africans to the New Amsterdam colony that would later become New York City.

(1) Why has there been controversy over the New York Times 1619 Project?

There has been controversy over assertions made in the New York Times’ 1619 Project on the impact of slavery on the history of the United States. I am not knowledgeable on everything discussed in the project report, particularly African American cultural contributions, but I think the history was basically very sound and the projects critics are off base. Three areas of contention are the role slavery played in fomenting the American Revolution, Abraham Lincoln’s attitude toward Black equality, and the white role in the struggle for African American Civil Rights. While there should always be legitimate disagreement about historical interpretation, I tend to side with Nikole Hannah-Jones and the 1619 Project.

American slaveholders lived in constant and hysterical fear of slave revolt and were always terrified that Great Britain would not provide adequate protection for their lives and property. In 1741, white New Yorkers invented a slave conspiracy and publicly executed more than two-dozen enslaved Africans in Foley Square. Tacky’s Rebellion in Jamaica in 1760, which took months to suppress and led to the death of sixty white planters and their families, sent shock waves through British North America.

As President, Abraham Lincoln preserved the nation, but he never believed in Black equality. In 1861 he endorsed the Corwin Amendment that would have prevented the federal government from interfering with slavery in the South. In his December 1862 State of the Union message, a month before issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln offered the South a deal which they rejected. He proposed keeping the slave system until 1900, that slaveholders be compensated when Blacks were freed, and that freed Africans would voluntarily be resettled in Africa, the Caribbean, and Central American colonies. In his second inaugural address just before he was assassinated, Abraham Lincoln offered amnesty to rebel states and slaveholders that would have left freedman technically free but in a perpetual state of subservience.

Last, there were many whites prominent in the African American Civil Rights movements after 1955 and Montgomery, but very few before except for leftist activists, and unfortunately, too many walked away from King and the Civil Rights movement after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

2) What are the top ways America benefited economically from the slave trade and from free labor? What about New York?

Before 1500 the world was regionalized with little interaction between people and regions. What is now the United States was sparsely settled by hundreds of indigenous groups including the Leni Lenape, an Algonquin people who lived in what would become the New York metropolitan area.

The Columbian Exchange launched the first wave of globalization and started the transformation of that world into the interconnected, globalized world we have today. At the core of what we call the Columbian Exchange was the trans-Atlantic Slave trade and the sale of slave produced commodities, sugar, tobacco, indigo, rice, and later cotton. Contemporary capitalism with all its institutional supports was the product of slavery. The slave trade led to the development of markets for exchange, regular shipping routes, limited liability corporations, and modern banking and insurance practices.

In colonial New Amsterdam and colonial New York enslaved Africans built the infrastructure of the settlement, the roads, the fortifications, the churches, the houses, and the docks. They cleared the fields and dredged the harbors.

In the 19th century, because it had a good harbor and was at the Northern edge of the coastal Gulf Stream current, New York became the center for the financing, refining, and transport of slave produced commodities around the world. Sugar from the Caribbean and cotton from the deep South were placed on coastal vessels and shipped to the Port of New York, loaded onto ocean going clipper ships, and then transported to Europe.

3) How did enslaved Africans change the landscape of New York City?

If we look at images of Manhattan Island before the coming of Europeans and Africans to the area, it was very different from today. The Wall Street slave market, established by the City Common Council in 1711 was on the corner of Pearl and Wall Street where ships docked at the time. Now the waterfront is two blocks further east. As Africans built the village, they actually expanded the physical city with landfill. We know that Africans built the original Wall Street wall and the subsequent Chambers Street wall which was the northern outpost of the city at the time of the American Revolution. A project by Trinity Church has established that enslaved African labor was used to build the original church and St. Paul’s Chapel where George Washington prayed and which still stands just south of City Hall.

4) Once slavery was abolished in New York City, how were African Americans still oppressed financially and politically?

Slavery ended in New York City and State gradually between 1799 and 1827. Essentially Africans were required to pay for their freedom through unpaid labor during this transitional time period. When finally freed, they received no compensation for their labor or the labor of their enslaved ancestors. Once free, even when they were able to acquire land, it was difficult for African Americans to prove ownership or protect their land from government seizure. One of the greatest injustices was the destruction of the largely African American Seneca Village in the 1850s when the city confiscated their land to build Central Park. If they had not been displaced, their land would be worth billions of dollars today. Politically, there were a series of discriminatory laws limiting the ability of African American men to vote; of course no women were allowed to vote.

5) Please describe how this financial oppression caused a lack of wealth for generations of African Americans.

Most of the financial injustice and the wealth gap we see today is the product of ongoing racial discrimination with roots in slavery but enacted into federal law in the 1930s and 1940s. The New Deal established the principle that federal programs would be administered by localities, which meant that even when African Americans were entitled to government support and jobs, local authorities could deny it to them. After World War II African American soldiers were entitled to GI Bill benefits, but were denied housing and mortgages by local banks and realtors creating all white suburbs.

Originally Social Security was not extended to agricultural and domestic workers, major occupations for Black workers in the 1930s. Social Security benefits are still denied to largely minority domestic and home health care workers who work off of the books. Many jobs held by African Americans were not covered under New Deal labor legislation and Blacks in the South were excluded from the programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps.

6) What is redlining and how did it affect African Americans in New York? How did segregation affect financial disparities? How did Jim Crow? Please connect how these practices developed financial disparities between black and white Americans for generations.

Banks and realtors reserved some areas for white homeowners and designated others for Blacks. On Long Island, Levittown had a clause in the sales agreement forbidding the resale or renting to Black families. Blacks were directed to declining areas like the town of Hempstead or areas prone to flooding like Lakeview. I grew up in a working-class tenement community in the southwest Bronx. My apartment building had 48 units and no Black families. This could not have been an accident. The only Black student in my class lived in public housing because his father was a veteran. There were a lot of Black veterans, but very few were sent to our neighborhood. Segregated neighborhoods also meant segregated schools. None of this was an accident.

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was heavily criticized for remarks about white gentrifiers from out-of-state who moving into former Black and Latino communities in Brooklyn and Harlem. The mock-outrage misdirected attention away from what is actually taking place. The new gentrifiers are not becoming parts of these communities. They are settlers displacing longtime residents. Partly as a result of a new wave of gentrification, homelessness in the city has reached its highest level since the Great Depression of the 1930s including over a hundred thousand students who attend New York City schools.

7) How did a person’s zip code affect their quality of life? How does it now?

Zip codes were introduced in 1963, so the world I grew up in was pre-Zip Code.

I think the three biggest impacts of where you grow up are the quality of housing, the quality of education, and access to work. In neighborhoods with deteriorating housing lead poisoning from paint and asthma exacerbated by rodent fecal matter and insect infestations are major problems. Children in these neighborhoods grow up with greater exposure to crime, violence, drug abuse and endemic poverty. Food tends to be lower quality because of the dearth of supermarkets and the abundance of fast-food joints. Schools tend to be lower functioning because teachers have to address all of the social problems in the communities, not just educational skills. For adults, they tend to have greater distances to travel to get to and from work, which essentially means hours of unpaid labor time.

8) How does access to education affect financial disparities between white and black communities?

According to a Newsday analysis of Long Island School District funding, Long Island’s wealthiest school districts outspend the poorest districts by more than $6,000 per student. Long Island school districts that spend the most per pupil include Port Jefferson in Suffolk County, where the student population is 87% white and Asian, and Locust Valley in Nassau County, where the student population is 80% white and Asian. On the other end of spending spectrum, the school districts that spend the least per pupil include Hempstead and Roosevelt in Nassau County where the student populations are at least 98% Black and Latino.

In New York City, parent associations in wealthier neighborhoods can raise $1,000 or more per student to subsidize education in their schools. At one elementary school in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn they raise $1,800 per child. Parents in the poorest communities are too busy earning a living to fund raise and too economically stressed to make donations. These dollars pay for a range of educational supplements and enrichments so that students who already have the most goodies at home also get the most goodies at school.

9) Why is it important to understand history when trying to understand the financial disparities between black and white communities in the U.S.?

It is too easy in the United States to blame poverty on the poor, their “culture,” and their supposed “bad choices.” When drug abuse was perceived of as an inner-city Black and Latino problem, it was criminalized and the solution was to build more prisons. Now that many white Midwestern and southern states have opioid epidemics, suddenly drug abuse is an illness that society must address.

10) What are some specific New York City examples of legislation or culture that impacted the financial divide between black and white families?

In New York urban renewal in the 1960s, that era’s name for gentrification, was also known as Negro removal, a term coined by James Baldwin. The 1949 federal Housing Act, the Taft-Ellender-Wagner Act, Robert Wagner was a New York Senator, provided cities with federal loans so they could acquire land and clear areas they deemed to be slums and then be developed by private companies. In the 1950s, the Manhattantown project on the Upper West Side condemned an African-American community so that developers could construct middle-class, meaning white, housing. Before it was destroyed, Manhattantown was home to a number of well-known Black musicians, writers, and artists including James Weldon Johnson, Arturo Schomburg, and Billie Holiday. Lincoln Center was part of the “Lincoln Square Renewal Project” headed by John D. Rockefeller III and Robert Moses. To build Lincoln Center, the largely African American San Juan Hill community was demolished. It was probably the most heavily populated African American community in Manhattan at that time.

11) What kind of New Yorker invested in the slave trade and how did that affect their family’s wealth for generations? Can you give us a profile of this type of person. What kind of family benefitted?

In the colonial era prominent slaveholders included the Van Cortlandt family, the Morris family, the Livingston family, and the Schuyler family, of which Alexander Hamilton’s wife and father-in-law were members. Major slaveholding families also invested in the slave trade. Francis Lewis of Queens County, who was a signer of the Declaration of Independence was a slave-trader.

12) What New York corporations benefited from slavery? Why does this matter today?

Moses Taylor was a sugar merchant with offices on South Street at the East River seaport, a finance capitalist, an industrialist, and a banker. He was a member of the New York City Chamber of Commerce and a major stockholder, board member or officer in firms that later merged with or developed into Citibank, Con Edison, Bethlehem Steel and ATT. Taylor earned a commission for brokering the sale of Cuban sugar in the port of New York and supervised the investment of profits by the sugar planters in United States banks, gas companies, railroads, and real estate. The Pennsylvania Railroad and the Long Island Railroad were built with profits from slave-produced commodities. Because of his success in the sugar trade, Moses Taylor became a member of the board of the City Bank in 1837 and served as its president from 1855 until his death. When he died in 1882, he was one of the richest men in the United States.

This article was originally published by History Network News.

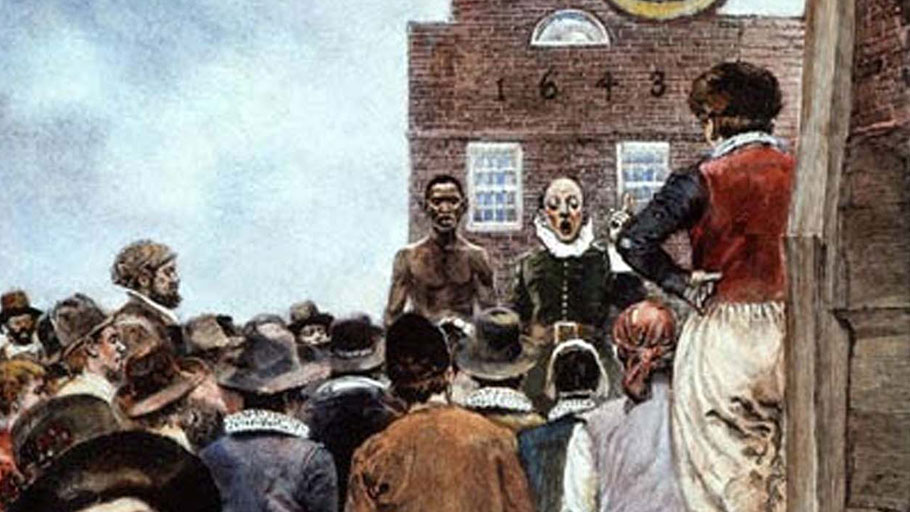

Featured image: First slave auction in New Amsterdam. Engraving after illustration by Howard Pyle, 1895. PD-US.