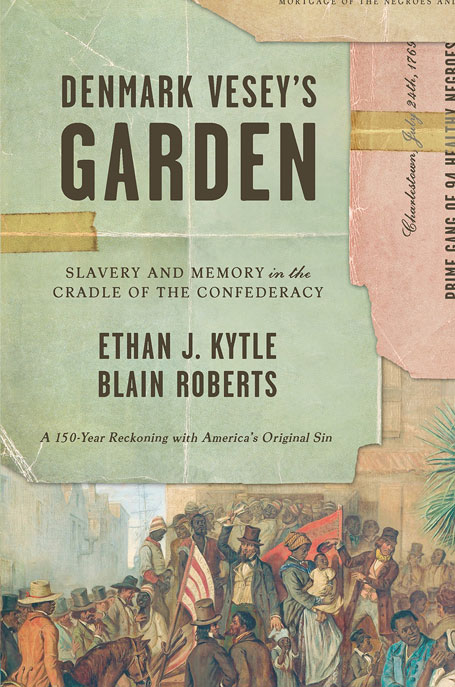

Denmark Vesey House at 56 Bull Street in Charleston, South Carolina. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

By Ashleigh Lawrence-Sanders, AAIHS —

The familiar refrain after the Emmanuel AME massacre on June 17, 2015, was that Dylann Roof, the murderer, was not from “here.” But as Ethan Kytle and Blain Roberts’ Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy aptly demonstrates, Roof’s understanding of history and memory in Charleston led him to that church; and his understanding was not alien to the sometimes violently, oft-contested memory of slavery in the city. Those wanting to understand why Charleston, a city intent on claiming the mantle of “America’s Most Historic City,” could be so inclined to ignore or whitewash certain aspects of its past can look no further than Denmark Vesey’s Garden. This rigorous and timely study of Charleston’s racially divided memory of slavery argues that the memory of slavery both undergirds the historical landscape and that the whitewashed memory of slavery in Charleston erases a vibrant history of African American memorialization. The book is structured chronologically in four sections stretching over 150 years: Emancipation and Reconstruction, Jim Crow Rising, Jim Crow Era, and Civil Rights Era and Beyond. Denmark Vesey, the free Black man who led an insurrection attempt in 1822, is one of the central catalysts for much of Charleston’s history and memory of slavery, as well as the whitewashing of it. The goal for Kytle and Roberts is beyond asking “how did we get here,” and rather why Charleston is an important place for understanding not just the memory of slavery, but a host of other issues related to the lives of African Americans today.

Beginning with chapters on Emancipation and Reconstruction, Kytle and Roberts highlight the unique role Black Charlestonians played in creating familiar rituals of remembrance. In carefully delineating the differences between memory and counter-memory, Kytle and Roberts avoid the trap of flattening African American memory as solely a reaction to white memory. Recounting the tale of the first Memorial Day or Decoration Day, the authors emphasize the key role African Americans played in memory creation. Indeed, as they state, “slavery and the Confederacy were dead and buried, and their apologists—outnumbered and outgunned—could do little more than carp about these changes and ridicule those who championed them” (61). The first section of the book builds on the argument advanced by Thavolia Glymph that white memory during this era was the counter-memory 1. Kytle and Roberts illuminate the joy and exuberance of recently freed people while also pointing to the dual purposes of these early celebrations. As they note, African Americans in the Lowcountry excitedly anticipated militia marches and parades led by African American war heroes, which were a “practical reminder of the military force that kept at bay the white paramilitary groups, including the Ku Klux Klan” (76) Black commemorations not only created narratives, but also had practical political purposes.

Kytle and Roberts also highlight the role that the memory of slavery played in the volatile elections during Reconstruction. Both Democrats and Republicans were keen on blaming the other for slavery. Republican politicians in particular levied the memory of slavery in what Kytle and Roberts call “shaking the shackles of slavery.” For African Americans, the palpable fear of returning to it animated African American life for decades after the end of Reconstruction. The violence of Redemption meant the end of many political and economic rights and freedoms. While it was no return to legal slavery, African Americans had cause to fear ex-Confederates’ desire to reinstate similar forms of social control.

By the late 19th century, the Lost Cause was in full swing and its proponents began to literally rewrite the history of both slavery and the Civil War. In Chapters 3 and 4, Kytle and Roberts explain the Lost Cause’s eventual stranglehold over the narrative about slavery in Charleston and the commemorative landscape. White Charlestonians began to build Charleston in the image of the Lost Cause narratives they held dear. It was during this era that the current Calhoun monument was erected, and that white Charlestonians dug in their heels on slavery not being the cause of the war. Kytle and Roberts emphasize the role of the local paper, the News and Courier, as well as the South Carolina Historical Society, the Ladies’ Memorial Association Committee (LMAC), the Survivors’ Association of Charleston, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in encouraging the myth of both “benign slavery” and involuntary slave owning. As Edward McCrady, a former Confederate officer, argued at a veterans meeting, slavery was “a burden imposed upon us by former generations of the world” and it “was not the cause of the war” (121). White Charlestonian women in particular, as they had in other localities, began to ensure that textbooks were not “biased against the South.”

Visibility of African American memory of slavery faded, not coincidentally, as the last years of substantial African American political power in the South did during the Jim Crow era. It was during this same era that Charleston cultivated its image as “America’s Most Historic City.” Kytle and Roberts’ most important contribution, perhaps, comes in this section as they explore the history of the Charleston tourism industry as both a site of retrenchment of whitewashed memories of slavery as well as an important landscape for a later, burgeoning counternarrative. Understanding the city’s tourism industry lends important insight into its preferred whitewashed southern tourism and the current stubbornness over its commemorative landscape. In the first half of the 20th century, white tourists that sought out Black histories would receive them through white cultural interpreters. Kytle and Roberts focus on one group in particular, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals(SPS) who performed spirituals in Lowcountry Gullah dialect for white audiences from across the globe. As Kytle and Roberts argue, the SPS and other groups and individuals like them who performed a form of Blackface without the actual skin darkening, “crafted a commemorative soundscape for Jim Crow Charleston” (198). Kytle and Roberts put it thusly: “just as the Old South planter claimed to provide for the material and spiritual needs of his inferior and uncivilized black family, SPS members posited themselves as the protectors of a unique musical legacy of a people who seemed bound and determined to forget it” (210).

Visibility of African American memory of slavery faded, not coincidentally, as the last years of substantial African American political power in the South did during the Jim Crow era. It was during this same era that Charleston cultivated its image as “America’s Most Historic City.” Kytle and Roberts’ most important contribution, perhaps, comes in this section as they explore the history of the Charleston tourism industry as both a site of retrenchment of whitewashed memories of slavery as well as an important landscape for a later, burgeoning counternarrative. Understanding the city’s tourism industry lends important insight into its preferred whitewashed southern tourism and the current stubbornness over its commemorative landscape. In the first half of the 20th century, white tourists that sought out Black histories would receive them through white cultural interpreters. Kytle and Roberts focus on one group in particular, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals(SPS) who performed spirituals in Lowcountry Gullah dialect for white audiences from across the globe. As Kytle and Roberts argue, the SPS and other groups and individuals like them who performed a form of Blackface without the actual skin darkening, “crafted a commemorative soundscape for Jim Crow Charleston” (198). Kytle and Roberts put it thusly: “just as the Old South planter claimed to provide for the material and spiritual needs of his inferior and uncivilized black family, SPS members posited themselves as the protectors of a unique musical legacy of a people who seemed bound and determined to forget it” (210).

The success of the SPS and others like them were predicated on the myth that Lowcountry African Americans themselves had no regard for these songs or stories and thus could not be trusted to interpret and share their own history. Again, Kytle and Roberts demonstrate that the social and political atmosphere had to change in order to gain mainstream visibility of African American memory. Civil Rights activists used the very spirituals that the SPS and others used to recall the “good ole days” of slavery and faithful servitude to cry for freedom, restoring them to their original roots. Local Black activists like Septima Clark and Esau Jenkins guaranteed that these spirituals were imbued with their original emancipatory purposes, and as Kytle and Roberts assert, “Jenkins became a bridge between the songs’ quasi-private use in the African American community and their public use with the civil rights movement” (267).

The Charleston Civil Rights Movement also inspired the creation of more Black-centered memory sites, Black tourism companies, and the integration of African American history into various plantation and mainstream tours around the Lowcountry. There was also the erection of a monument to Denmark Vesey in 2014, ironically in Hampton Park, after decades of activism and pushback. As Kytle and Roberts point out, Roof visited some of these revamped sites, including the McLeod Plantation, which they call “the best site to visit for an honest, unvarnished account of slavery” (338). Yet Roof, as they acknowledge, “sought, and found, historical justification for a return to white supremacy.” (338) Here Kytle and Roberts pose an important and complicated question that has plagued scholars and activists alike in the past few years: “what does it mean when, in the year 2015 someone can so blithely ignore unvarnished memories of slavery and embrace whitewashed ones to justify killing black people?” (338). What does it mean that this continues? Kytle and Roberts do not have the answers, but they reveal the incredible stakes. Despite the changes in the past three years, Charleston’s commemorative landscape does not accurately reflect the importance and influence of African Americans and African American memory of slavery. It continues to mirror the dominance that one group, white Charlestonians, have enjoyed in control of this narrative and the accompanying landscape. This segregated and whitewashed memory was present during the vote on the Calhoun monument as well as the recent, narrow vote to apologize for slavery. Kytle and Roberts contend in Denmark Vesey’s Garden that memory continues to be about power, and how those who have it wield it to serve their own goals, memories, and histories. The “enduring misunderstandings born from Lost Cause mythology,”(348) as they put it, have real consequences for the lives of African Americans. It remains to be seen if this gradual and still controversial inclusive commemorative landscape may be an actual step forward for tangible changes for the lives of African Americans in Charleston.

- Glymph, Thavolia. “Liberty Dearly Bought: The Making of Civil War Memory in African American Communities in the South.” in Time Longer than Rope: A Century of African American Activism 1850-1950. New York: NYU Press, 2003.